A Game of Snakes and Ladders: Evaluating the Engagement of Patients in Research

Episode 3, featuring Audrey L'Esperance, Anne Marie Lavasseur, and Carolyn Canfield.

Meet Our Guests

Audrey L'Espérance is Assistant Professor of Health and Social Services Management at the École nationale d'administration publique (ÉNAP) in Montreal. At the intersection of clinical, professional and research environments, she has worked on evaluative research projects and developed management practices that emphasize partnerships with patients and the public in several areas of health and social services. She is currently pursuing a research program on the inclusion and integration of citizen and expert knowledge in decision-making in health and social services.

Mary Anne Levasseur is the Peer Coordinator, Caring Community Project, of the Canada Research Chair in Partnership with Patients and Communities, and a Citizen-Partner-Researcher team member of the Interdisciplinary Chair in Health and Social Services for Rural Populations, University of Quebec at Rimouski. She has extensive experience working with families and caregivers in peer support groups, notably as a family peer support facilitator for family support groups in First Episode of Psychosis (PEP) programs. She has also facilitated family peer support training groups. Mary Anne is an active peer researcher and knowledge user in various research projects with a focus on family caregivers and patient partners. Her interest in improving the healthcare experience is grounded in her role of caregiver and advocate for her son.

Carolyn Canfield is a citizen-patient who volunteers across Canada and internationally to expand system partnerships with patients, carers and communities. Her work since 2008 earned her recognition as Canada’s first Patient Safety Champion and faculty appointment at the University of British Columbia. She actively partners in research here and abroad.

Contact the hosts: Anna and Bryn

Bryn Robinson

Thank you, everyone, for joining us on As PER Usual, a podcast that explores the current state of patient engagement in Canadian research, and how to make it better. My name's Bryn Robinson, and today, we've got a great panel of guests to talk all about evaluation.

In our study, participants noted the continuing lack of benefits, value outcomes and impacts of patient engagement and research. And that's problematic, because we need the evidence to support patient engagement and research to show that it is necessary, to justify its’ cost to funders, and to help ensure it is systemic and sustainable in the long term.

Anna Chudyk

Yup, you're absolutely right, Bryn. Those are definitely some key issues with the current state of evaluation of patient engagement in research.

So what does a preferred future state look like, you ask?

Well, according to our study participants, in a preferred future state, evaluation and measurement of the process and impacts of patient engagement and research are commonplace. This contributes to the building of an evidence base that is used to guide best practices, justify the cost of patient engagement to funders, including ultimately taxpayers, and ensure the long-term sustainability of patient engagement and research.

Some factors that contribute to achieving this preferred future state include:

Widespread agreement and recognition of the indicators and metrics used to evaluate the outcomes of patient engagement and research, as well as its’ “success”;

Research that regularly focuses on the process of engagement - instead of, let's say, just looking at the health outcomes of a study - and;

Manuscript requirements that have evolved to better support the full reporting of engagement methods.

Alright. So clearly, there's a fair bit to do. And with us today, we have 3 guests that are going to tell us about the amazing work that they are doing to help guide the evaluation of patient engagement and research in Canada.

Specifically, we have Dr. Audrey L’Espérance, Carolyn Canfield, and Mary Anne Levasseur. Thank you so much for joining us here today before we hear more about your research.

Could you please start us off by each telling us a bit about yourselves in terms of your background, as it pertains to research and experiences you'll be sharing today?

So why don't we, let's say, start with Carolyn, followed by Mary Anne, and then Audrey.

Carolyn Canfield

Hi, Anna. Hi, Bryn. It's just wonderful to be here to join you.

So I came into healthcare unwillingly, if you like. It was a tragic event in healthcare failure, and that piqued my curiosity because I was surprised that I was the only one who was interested in finding out what had happened, and learning from it, putting experience into some kind of learning impact.

I had never realized that there was such a thing as patient safety, what patients are unsafe. So my curiosity drove me to learn more and more about healthcare - and as I did, I, of course, learned about increasing patterns of patients getting involved in healthcare. I was very fortunate in 2014 to be offered a faculty position in the Department of Family Practice at the University of British Columbia (UBC). My orientation was around teaching my perspectives on patient safety, and I was invited to teach in the undergraduate medical program - patient safety, that theme.

I got into the research side of patient involvement really through opportunistic relationships. I had relationships with people who were involved in research and in practice improvement. It really came from the quality of improvement side of things, and that blurring between what's quality improvement, and what's research, was a vexatious problem 5 to 8 years ago. I mean, people still thought of it as an issue. I think it's really dissolved now, and it's blended. We see many more people who are involved in research that very closely addresses practice improvement - that “learning health system” is really fueling, I think, that pattern. I've been involved in international research projects that look at whole system concepts, resilience in a system engineering point of view, right down to research in evaluating practice improvement.

And so my work is primarily as a citizen patient in the Department of Family Practice in the Faculty of Medicine at UBC.

Mary Anne Levasseur

So I'll take it from here. Thanks, Anna and Bryn, for having me here today with you and this wonderful panel.

If you would have asked me some 20 years ago, if I thought I would be sitting here today and doing this kind of work, I would have said, “Absolutely not. I don't do any of that.” I come from a corporate background, and the way I entered this field was through caregiving for my son, who had a serious mental illness - developed into a serious mental illness over time - and so through caregiving, I became more and more involved with dealing with the health system.

I would say that normally, I think that, for the most part, people don't deal with the health system unless they have to. What happens after that is usually up to the person, and I would think that most people leave the system after they've had their experience in the system with healthcare for themselves or for others. But because my son was dealing in healthcare for an extended period of time, and he really needed help in advocating for himself to get the proper resources for himself, I found that I was spending more and more time helping him to manage that, as he being a young adult. At a certain point I said, “This isn't working anymore. I think I need to leave my position for the time being.”

I thought it would be temporary, and I'll spend the next 6 months or a year helping, getting him back on his feet, and really advocating for him in healthcare.

And so, around 2007, I entered the chaotic world of mental health and the mental health system, and from there, I did help my son to get appropriate help and services. I advocated for him, and I learned a lot about navigating the mental health system. In 2011, the coordinator of my son's program at the hospital asked a group of us parents if we wanted to meet together, to discuss among each other our journey with our young people in caregiving and helping them through their illness.

We ended up meeting together, and I volunteered to facilitate group meetings, and I never turned back from there. I ended up being the Family Peer Support Facilitator at that clinic for the next 10 years, and in doing that, I also got involved more with the research side of my son's illness, with clinicians and researchers at the clinic.

Then I was asked in 2013 if I wanted to be a representative - even though you can't be representative of family caregivers - in a national research project. At that time, Canadian Institutes of Health Research had just initiated shortly before their Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) and I think we were going to be the first national research network in youth mental health. I agreed, and the rest is history; I started working with this huge group of people across what is now 17 sites in Canada, and we worked with many different populations. I met hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of people through the project, and I learned the ropes about research and what it means, and being what I call myself now as a citizen partner and peer researcher, that's what developed.

Through that project, I was able to jump onto other projects, are invited onto other projects in this new career of my own, and I never went back to the corporate network.

So that's how I'm here today. I'm still working actively in several different research projects in family engagement and family peer support. I co-founded the national community practice in mental health for family peer support workers. I'm also a co-founding member of Patient Advisors Network. I work with several different universities in Quebec, and the rest of Canada.

I'm just continuing to develop this career of mine, and sometimes wishing I had another 20 years to do so. Not sure how many years I've left, but 20 seems like a good number! But that's what I'm doing right now.

Audrey L'Espérance

Thank you again for the invitation and for having us, and having this discussion about evaluation. I think it's paramount to have that discussion more broadly and more deeply.

I’m Audrey L'Espérance, I’m an assistant professor at École nationale d'administration publique. My expertise is in health and social services management, but more specifically, everything patient partnership oriented, from patient partnership in research, but also in healthcare and a little bit in medical education as well.

Just for a little story: I'm actually a political scientist, so I come from the social science and the political world. I've always been interested in understanding how lived experience, and expertise, and the match and the bridge between those two types of knowledge, are actually changing and influencing public policy making. Public policy can be very broad, like lawmaking or big program systems, but it can also be really tiny clinical practices, or ways we enter in relationships and very intimate settings. And that's what I did for my studies, but also in the first years of my career.

I've been, for 6 years and a half, a part of the team of the Center of Excellence on Partnership with Patients and the Public, and that's how I got to meet Carolyn and Mary Anne, and several other patient partners. Until then, I would say that patient partnership, for me, was one form or one piece of what I was calling patient advocacy, which is very large, and can go into forms of activism, to the partnership we talk about in research, and co-leadership of projects like Mary Anne was mentioning earlier.

I entered this work with my eyes and my ears wide open, trying to understand what was the difference in how we were conceiving partnership and health research, because I was coming from a social science background, where citizens are part of what we do in some way.

A lot of participatory research was ongoing around me for a long time, and so it was quite surprising, somehow, to see some of my colleagues in health research having so many resistance or questions, or even like a bit of misunderstanding of what partnership can bring to their research.

For the 10 past years, I've been coming with both my political science background and also- I’m very fond of of all methods. I'm kind of a geek for methods, and mostly qualitative and deliberate methods, which are also linked to partnership and evaluation for me. It's almost like a pathway to bridge both what we're trying to do more philosophically with patient engagement (and patient partnership more broadly), and what we're trying to achieve in terms of transformations in the system. It's interesting to look at it from that perspective of learning together, and that's the title of our our framework.

And I say ours, because I'm so grateful to have been co-building this with Mary Anne and Carolyn all the way through.

Anna

Thank you so much for sharing with the listeners a little bit about yourself, and about the many different ways that you came into the patient engagement in research world.

It definitely sounds like any one of you could have been on any one of you could have been on any one of our podcast topics, so I can't wait to hear all that you have to say about evaluation.

With that, Audrey, would you like to share with the listener about the framework that you and your group developed for the evaluation of patient engagement in research, including what you did and what you found. And then, Maryanne and Carolyn feel free to jump in at any point as well, and share your experiences, takeaways, perspectives.

Audrey

It's a bit difficult to tell you a story of three years in a few minutes, but I'll try to do that.

So in 2007, with the team in the Center of Excellence on Partnership with Patients and the Public, we - well, Antoine Boivin - we conducted a systematic review of evaluation tools. At the time the question, in the Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) community, the discussion was about, and the questions were raised, about what was available to evaluate patient engagement. We knew a few tools, and we wanted to know, “Is there better ways or better tools, or are there some tools that could be transferred or used more broadly in Canada?”

That systematic review got us to build a very fancy toolkit, but we actually didn't know what we were building. We needed that blueprint, and that actually is maybe the biggest result of that systematic review, was that we ended up with a lot of tools - but not one-size-fits-all type of tools that people were looking for.

So we started thinking and talking, with many SPOR entities, the SPOR SUPPORT Unit for networks, people at CIHR, patient partners we know that were involved in SPOR entities. We built this idea of co-building, and through deliberative methods, different types of methods, an evaluation framework. So we will be able to know what we are building, what type of transformation we're looking for, but also using the tools in the the most relevant way.

We started this project in 200- yeah, I think the first conversation started in 2018, and we actually launched the model in 2023 - so a one-year project transformed.

I think transformation is a word that we’re embracing a lot in the team, both because it's part of the framework, but also because we feel like the project changed. And I can tell that I personally transformed in many ways during- even moving from one position to another position in my career, or having kids. I had a baby during that time. It's just like life intertwined with the project, which I like, and what which I like to tell that story, too, because it's part of how we build the thing, but also it is, I think, a reflection of the relationships we try to build during the project with the different participants.

So we had 141 participants across the phases of the project, all from different sides and provinces and territories of Canada. We were so grateful to have all these participants to the three phases, and the first phrase was a consensus building exercise on questions that were really broad: “What do you think successful patient engagement looks like in research? How can we consider that it's a success? What does it look like for you? Are the patient engagement principles that were written in 2014 in the SPOR Patient Engagement framework still relevant? Are they still lived and living principles?”

We identified, through that phase, 20 different dimensions that are attached to the development and preparation teams need to have and put in place before starting a project - through process dimensions, how we do patient engagement, basically, and then transformations and the impact.

This is maybe one of the biggest and boldest and most important result of that first phase is the underlined importance that participants put on transformation. Both researchers and patient partners - all participants - told us that if we are engaging for just for the sake of engaging, it's not enough. So we can have the best process. We can be the most prepared environment. If we're not changing and transforming research practices and then healthcare, we're not achieving what we are supposed to achieve. So that's one very big piece.

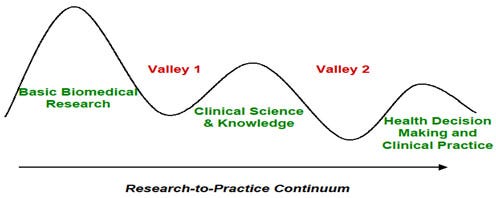

The other result was also that a process of engagement is not linear, and partnership is very messy, and a bit like a “Snakes and Ladders”-type of process you go on. You move on, and then sometimes you slip and you have to go back, and it's maybe sometimes longer, or you have to revise plans. And but that's the beauty of it, and that's the importance of it.

We wanted to build a model that wasn't linear and showed that importance of discussion and muddling through.

I think that's one very big element. Then we did lists of indicators. So we had- we were very fortunate because in the literature, we had tons of people that did systematic reviews of indicators of success for patient engagement. So we matched the dimensions; we identified two lists of indicators, but lists with a lot of intensity, because the lists were super long. People that participated in our Delphi, they knew it was a very long questionnaire with tons of indicators. They did an awesome work of participating and getting us to shorten that list, and also identify which of these indicators are the necessary ones - the “must haves”, and also the “nice to haves”.

That actually told us that evaluation is- we need to create capacities also. You might, as a project, as a group, as a team, have lower capacity to evaluate patient engagement, and that’s fine - but if you want to grow in your capacity, you could actually choose a more numerous number of indicators. You can actually evaluate more dimensions.

Finally, the last phase was kind of intertwined in between the two first phases. It's an equity-based discussion and the dialogue we had with experts. And here, when I'm saying experts, it's not just researchers that have like specialties and expertise, but also patient partners that work with them very closely. Through the project we were getting the questionnaire done, and I was traveling with a questionnaire and all of our committees to just check if, for indigenous communities, it made sense, if the language was right, if the way we formulated things, if there were indicators that were completely missing and that we would need to add.

We did that with five different, what we call, equity-based experts committees, and to make sure that the biggest, the broadest, most represented communities within SPOR, because that was the groups we were working for- had a say on how we built and reported back on some of the framework. Then finally, we worked with a graphic designer to actually translate all of these really great results that were pretty boring when we’re looking at them, in a way that was conveying the spirit, but also the the complexity and the simplicity or the relationship underneath the model, and trying to make sure that people felt that they were able to take on and use that tool.

It was not our tool, and it was not for only the sake of research. It was also- the broadest goal was to get people to start evaluating, and for that we needed to have a tool that was homey, nice, accessible, useable.

Carolyn

I'd like to add to what what Audrey's story has been, with a perspective.

I don't think I'm telling tales out of school, Mary Anne- when Mary Anne and I first came into the project as links to the Patient Advisors Network, which was a partner in the formal application for funding and the grant for this project, Mary Anne and I attended a few of the initial meetings, and we rolled our eyes and thought, “How is this going to happen?”

This is such a big undertaking; it's a massive thing to create an evaluation framework for patient involvement in research, and we thought, “Well, we're absolutely in for participating. But this is gonna be something to watch. What a timetable!”

And I think that what we underestimated, or didn't comprehend - what is one of the extraordinary aspects of this project, which Audrey's narrative has really illustrated, is that this is crowdsourced. This isn't top down; “Here's the theory that supports evaluation, here's the the client focus on value.” This is from the participants, and a large number of participants who have been active in every aspect of patient partnership and research, so that, in the course of our project and with the interruption of COVID, we got more time, which was invaluable.

Audrey has talked about the extended surveys we had with our Delphi. All we asked of our participants, which was extraordinary- come back again and again, and rank these indicators, what we were actually doing. And I think I have the perspective of a few months since the launch of the product framework- what we were, I think, did, in fact, was building relationships and Audrey's talked about the theme of transformation as big, really compelling. This is what we experienced in this project. It's what our participants have experienced in their research projects. What they contributed- their perspective reflects this, this astonishment at transformation, but I think the other, and maybe the most basic part of the Learning Together Framework, is that it’s about building relationships, and they happen through the entire lifecycle of a project and in fact, inform everybody's participation in the next project.

I think we've seen this through the history of patient-partnered research - that once people have done it, they won't do their work in a different way. They won't go back to old ways; that this relationship building is so good for the research community, in Canada. We build ways of communicating with each other.

One of the great, well, the classic failing of research is the Valley of Death. Between publishing your paper with your findings and seeing it impact reality.

If you're involved in true partnership, in a rich partnership, with people of many different perspectives, through that project you are transformed. And part of that experience of transformation is really it ties very well in connecting up with practice. So, you become a proselytizer for the work that you've done. You have been that engaged in those relationships you have been transformed by your participation and by the outcome.

So I think in some ways, Audrey, that by involving this large number of very experienced people across Canada in so many different facets, we also have engaged them, as in the spread and scale. In the use and adaptation of this framework, this isn't something that's fixed; we expect it to be adapted, not only in its framework now, but added to and changed, and to be a living tool in creating better research.

Bryn

Mary Anne, did you have anything you wanted to add, or…?

Mary Anne

Well, what I would say, to what Audrey and Carolyn have spoken about so eloquently with regard to this project, is that something that Audrey said stuck with me, that we worked on it; we worked really on this one year project for 5 years, basically, from start to finish.

And we developed an incredible framework through the hard work and participation of many - a couple hundred people or more - throughout the process. I think my colleagues would agree with me that, at the end of the day, we realized we had just finished Step One. That this framework that was built, in fact, was more than just an evaluation framework to measure patient engagement in research and related, but rather it was a philosophical framework for the way we look at how we interact with patients in the real world. Even patients and caregivers are used to the way healthcare professionals and researchers and related deal with them when they have a health priority, a health issue.

But this framework allows us to look at the the trajectory of healthcare from the perspective of the patient, and we can realize that, for the patient, the journey is not a discrete journey of different steps. It's part of their life. If they come into the system as part of their life, because they have a need that needs to be responded to, and they go through the process as one long fluid trajectory until they get what they need, if they can or not.

By the same token, healthcare workers who are in healthcare and research and policy, and so on, see only a part of that patient journey from their own specialized perspective. By inviting patients and caregivers to actually contribute actively and collaborate throughout part of their journey with the people who are having trying to help them, they allow a wider perspective on what we need to do to improve healthcare outcomes.

I learned that, in this project, on a personal level as well as a research or a professional level, because when I entered the project, what attracted me to the project was that we are going to build an evaluation framework. I love that kind of stuff - I like order, organization, and having already dealt in a national research project with hundreds of people for the previous five years where it was always a hot mess, and nobody in my mind knew what they were doing. I come from a very ordered background. So in my mind people were trying different things that were, or were not, working. Sometimes it was documented, sometimes it wasn't. I just needed more order. This project was the answer? And I came into the project, and I said, “Yes, for once we're going to develop an evaluation framework, a standard that would allow us to involve patients and work with patients and caregivers in a way that we can be assured that we've really checked all the boxes.”

But guess what?

You can't check all the boxes. You can't check ANY box. In fact, a standardized framework for patient engagement is an oxymoron. You can't have standardized patient engagement. It doesn't work together. Patient engagement is a unique process and a unique experience both for the patient and the healthcare worker, or related.

So how can we build something like that? Of course it's all about the transformation. It has to be about the end result in your experience, and the patient experience, and the way transformation is elaborated or expanded upon is through the natural knowledge mobilization of the patient to both care for himself, or herself, and spread that knowledge to others.

And so this framework, this evaluation for work - in my mind - is to share with everyone who's interested. The philosophy behind sharing the part of the life experience of a person who comes into a system and says, “I need your help.”

Bryn

I'm hearing a couple of themes throughout what you're all saying, and I think it’s actually giving me pause. I think a lot of what we read about is very focused on this idea of standardized patient engagement evaluation - that there is some sort of order, that there is some amongst the chaos, as you say. And Audrey, you mentioned, too, that you thought only this- there’s no “one-size-fits-all”, that you went through the literature, you went through the research, and it does seem a bit like an oxymoron to ask, “What does pay standardized patient engagement evaluation look like?”, but it sounds like it might not exist. Or maybe it's that philosophy that's the standard?

I guess, two-part question:

Is there is such a thing? I think we know. Maybe I've heard the answer.

But what should people know that maybe want to incorporate some elements, and maybe are also feeling overwhelmed and don't know where to start when it comes to evaluation. How do you start incorporating that into your research?

Mary Anne

I think I'll just answer the second part of your question, and leave that the first part to others. But for me, when we talk about the philosophical standard, I think that's okay to say, “I don't think there's anything wrong with our-” in fact, there are a lot of benefits to create a new standard, a new level of being, in terms of how we deal with each other, in terms of how we relate to each other in something so important as healthcare or healthcare research.

So I think to answer the second part, it’s the philosophy that is the new standard, the philosophy of really collaborating with each other and assuring the patient that it's okay for them to be responsible for their own healthcare, and to collaborate with healthcare people to get what they need.

So that part, yes, there is a standard, I think, a new standard to be worked on, but for the first part, not so sure.

Bryn

That's okay! Carolyn. Audrey, do you have any…?

Carolyn

Yeah, I would. I'd like to elaborate a little bit on what Mary Anne was referring to, of the philosophy of care.

You know, we talk about evaluation, so where's the value? Well, in patient partnership and research, just look around. It's no longer an issue. We look at the tens of thousands of citizen patients now who are participating in partnerships of all kinds with the healthcare system, and I spoke a little bit about the- my idea that there's a kind of blurring between practice improvement and research.

So if we think about our way, our concepts around research, and compare it with concepts around healthcare policy and practice, and how that's evolved over the last- I don't know, 15 years is how long I've been involved with it - when I first came in, it was about patient-centered care, and very often times there'd be a schematic with a stick person patient in the center, and all these specialists circled around them, and obviously the patient’s in the centre. This is ludricrous.

Health care is not a product to deliver. It's not an assembly line, standardized issue. It's about relationships. It's about continuity over an episode of care. Even if it's an hour in someone's office, it's that relationship of trust that is the glue that makes patient care connections. How could you possibly understand any aspect of healthcare without understanding the patient's perspective? It's like one hand clapping. You can’t do it.

So when I first came in, and I think this is true- if we look back 10 years ago, 15 years ago, at research, honoring expertise, honoring the professional point of view, and I would hear initially - and I think Mary Anne has as well - “No, no, Carolyn,” as I’m being patted on the head, “We're all patients. So that's how we represent patients in our operation in our research.”

Well, we're not all patients. Patients have a huge variety of views, but it's a distinct view. It's not shared with the professional view. Yes, of course, people can have experiences as patients, and also be in the professional world. But it is so important to have that that distinct patient perspective to contribute to a fuller understanding of what health care is. How can you do this without embedding the patient?

It's not just of asking for patient advisory roles on a research committee; it really is embedding the patient in each step of the project. So in identifying research priorities, in designing research projects themselves, in planning them out, in defining what kind of data collection, what kind of analysis, what kind of of recruitment, in actually conducting the research involving patients as team members, in conducting the actual steps of the research. Bringing that patient perspective into the announcement, into the writing and in an active way, in those steps, not as advisors, not in proofreading the final report. And then, as I've referenced before, in spreading the information through networks, because patients have very distinct networks in the healthcare system that do involve people who are professionals, as well as many patients, and organizations, and that spreads into society as well. So as we've gotten involved in this co-production with patients on the research team, it really highlights some of the issues around power imbalances, and remuneration, and so on.

These are the active issues today. I don't expect that there'll be active issues in 10 years. I think we're progressing that quickly and modifying the way we do research.

So the issues that we're looking at today that we’re, I think, all struggling with, and we are fully aware of in this evaluation framework is, “How can we do this patient-centered thing, this view of health care as relational, without inclusiveness and without highly diverse patients being involved well in practice?”

Looking back, looking at the state of research now, most partnership situations are really bringing in patients as proxies in professional roles, it's bringing in people who can act as if they were researchers.

I've been captivated by a big idea from a physician in the UK and Wales, Dr. Julian Tudor Hart, who invented back in 1971 something called the Inverse Care Law, which says that those most in need of care are least likely to get it and I think there's a corollary in research where those in most need of participating as participants in research are least likely to get in the doors that we provide for research. So it's incumbent on us to develop new forms of partnership. And I think this is also in parallel with the healthcare system. Yes, we need to lead with relationship building before a project is even defined. Establishing relationships with patients, with individuals, but, more importantly, with communities. I think that this reflects the need to have continuity of relationships that build on the individual relationships.

So when we look at the challenges of measuring impact on health, almost like the next step, we're discovering, especially with marginalized communities, social determinants. That's where we're realizing that the healthcare system and the social system have to have system-to-system interactions - have to be connected, have to have relationships - and, I hope, have the opportunity to transform with that collaboration with bringing in those perspectives from different areas.

I mean, we intersect as individuals. We intersect with each other in a community, and and that's very different than how we intersect as individual-to-individual.

So I think healthcare policy is really evolving in the same direction as research is evolving. I think we feed each other, and the bottom line really is a transformation. And I think that's where all of us are hoping the quality of our research is leading. People are changed. People are saying that they won't do things any other way ever again, and our institutions are research structures are really reflecting that recognition that it takes an intermingling of perspectives and an embrace of the unknown, of not knowing where you're going, and having good handholds, good frameworks like this one, to ensure that you aren't leaving things out.

I think that that's really the power of the Learning Together Framework is that it's opportunity at every stage in research to reflect on values, reflect on relationships, reflect on facets of interacting, to ensure that you're getting the most from the participants that you can attract.

Audrey

Yeah, I'm gonna it's a nice segue to what I wanted to say. I think this is also a result of the whole process of this project, and not just the framework itself, which could actually, could have been only a tool, and a tool for evaluation. We ended up with that result: that actually the framework is as much a tool for evaluation as a tool for planning and reflecting on relationship during a project. And I think these three different purposes of the framework are as important and as actually paramount to one another than the evaluation on itself.

I’m going to explain what I mean.

If you're not preparing and planning for partnership, you're actually missing out on many different things. Planning doesn't mean that doesn't mean you'll have all the dots organized, and all these steps that are- it doesn't mean that you're gonna actually follow each and every step of your planning. However, it's gonna help you reflect during, reflect on what you had planned for and didn't happen, reflect on the relationship that actually happened or didn't.

By the way, the first patient partner was involved, and co-designed the method and the protocol with me. Alex actually left for personal reasons during the pandemic, and it's because he left that I reached out directly to Carolyn and Mary Anne, who were already involved, to say, “Hey, I lost my collaborator, my partner, my duo is now me alone. I need to have people surrounding me during, and I'm not going to do this project without patients involved.”

And they said yes, and the co-construction continued.

I didn't expect that. That wasn't in the planning. That change of plan happened, but I was able to understand the changes and how it affects research, how it affects my team, how we need to reorganize because the planning was done first. I think that the framework was built towards this idea - that we need to match evaluation with the nature of engagement, the nature of what is patient partnership.

And this is one thing that we tend to actually forget, because evaluation means many different things. It can mean evaluation, and health research is very circumscribed; it’s evaluation of impact, and it comes at a very different timing than when we do - I come from political science - when we do program evaluations, and in social innovation, they do more developmental types of evaluation. There are different approaches to evaluation, because we are evaluating different things. Different objects, different dynamics. Patient engagement is an ever-moving, ever-changing, relational, mostly reciprocal, and if it's done well, dynamic - and it needs an evolving, adapted way of evaluating. This is a change of culture drastically in health research, because evaluation is seen as a very specific manner, structured. That standardized idea that you mentioned comes from that idea attached to evaluation.

But evaluation, if we look in different types of models, disciplines outside the scope of, health science, we can see that it takes many forms. There are different approaches. We try to decolonize evaluation as much as we can. For me, this is, in more science-y words, it's like we need to match ontology with methodology.

We cannot go on thinking about evaluation in an instrumental way. Patient engagement and patient partnership is not an instrument for better research. It is not a function, it is an integrated mechanism of learning, which is why we chose that label, that name of “Learning Together”, because it becomes a social learning mechanism and it's embedded in the research.

The next steps would be that we would integrate the framework, not just in the evaluation of a project, but in the evaluation of the whole conduct of research, which is a different way of thinking. And it also speaks to, and asks for, more support for engagement evaluation because it's harder to do. It's a social dynamic. I cannot tell you that patient engagement has direct effect on healthcare. I would love to; that’s not feasible. However, we can build the knowledge along the way that we'll lead us to show the effect.

If people can see the “Learning Together Framework”, it looks like a pathway - that's what the pathway is all about: Start your evaluation day one by planning and reflecting on your actions in your relationship. From day one, keep track. Keeping track doesn't mean to have fancy different tools that are very hard to implement, and very heavy on the shoulders of your team. No, you probably have those integrated already. Take 5 minutes each meeting to just talk about your relationships. We did that. Some days we wouldn't go on Zoom, and we're not feeling so well. We knew, we shared; sometimes our meetings took longer, because we actually wanted to share some personal stuff, and it's through that that actually, we were able to also see what wasn't going right in our team.

It would be a lie to tell you that it was always comfortable, and people that do patient engagement right know that it's not always comfortable, both for patient partners and researchers - and mostly for researchers, I think because we get challenged, with all of this structure and rigor, and institutional imperatives that we get to navigate and get to used to. So there's something challenging about it, but the challenges are where you actually sit down and write down an observation. “Today wasn't easy. I had to make this type of a decision.” It's not, it's probably in your notes, it's probably in your lab notes. It's things that can be integrated into our practice. And this is how our research practice will be influenced by engagement. Evaluation will be one of these things that we will embed in our way of doing research that will help us go through.

Anyways, that's what we've learned. I think the most about building this project, it's not about the evaluation at the end. If we are just looking at the impacts or transformation, we won't even able to do it, we won't ever be able to measure. We’ll do maybe 10% of what we can really do by planning, reflecting during, and improving during, and then finding out what changed and what improved in our research, in our teams, and also eventually what it will bring in the healthcare system.

I just wanna add one mini thing that a colleague of mine, confided, told me about the project that she led with patient partners. She told me that the biggest transformation she saw in herself is the fact that now she's talking with media, and she's bringing- she told me, “I became an advocate. I cannot stay in my office anymore. I need to speak about these things. I need to, if they're interviews.”

Well, what this is? A change in practice. This is a change, a drastic change in how that researcher is actually interacting and diffusing their research. Same with clinical researchers that told me along the way, when I was evaluating different types of projects done in partnership, “I completely changed the way I practice in the clinic.” That's a big change. “I don't interact with my patients the same way, because I did research with patient partners.” Enormous.

We don't collect, we don't keep track of those changes - we don't even ask researchers about those. Well, let's start and ask. And it's not about, it’s actually the framework is created, and we're trying to convey and diffuse the idea that the framework is not a tool to apply - it's a tool to reflect and to build your own evaluation framework. You might want to take a look at just one piece, and actually go deep into that piece, that dimension. Let’s say, communication is very key; you want to go deep on communication, just look at it very deeply in your team. That's evaluation. You want to do the whole big mammoth? That is the framework. Go ahead.

But build the time and do it in partnership with, because that's another thing, you’re not evaluating with this tool without patient partners, because there is a need to build reciprocity and all of the data that you will bring and collect.

If you don't see the change in the transformation for both researchers and patient partners, you're not transforming. You might be changing something, it might be important, but if there's not that reciprocity for me, it just - and that's not something that I say, it's something that I heard from the participants to this project.

Anna

Thanks so much for these deep reflections, Audrey. I find whenever we talk, my thinking is always pushed that much further about patient engagement in research.

And Mary Anne and Carolyn, I feel the same way about you, and I really like that the key message, and something that is one of my favorite things about being involved in patient engagement and research, is that a lot of it is about understanding the essence of why you're engaging, what it means to engage, and how to engage.

And through these conversations, you guys have helped me to really deepen my understanding of what patient engagement is at its core and make important linkages to patient engagement in research, and patient engagement in care, which obviously both feed into each other and truly, you can't measure something unless you first understand what it is. That's, I think, another benefit that the listeners will have from what you guys shared with us today - that better understanding of the need to understand what patient engagement it is, and fundamentally, it's the relationships and the reciprocity, and working together to transform health care. But through that reciprocity, you are also being changed as a person, as a patient, as a researcher.

And it's important to plan for what you're going to do together. And then see that growth alongside each other so that you can know it. And that's a important outcome in and of itself, of patient engagement and research. So I'm sure everybody's who's listening to it today, I'll be excited because they'll know it's not just a boring tool that I look at. But first it's really an understanding. It's a way of being, and then through that it's moving to your health framework and helping, be it, “I'm a big, big big place with a lot of capacity, so I can evaluate all these different aspects,” or maybe, “We're smaller, we have limited capacity, or we're interested in that one thing, and that is okay.”

So thank you, I can't wait to learn more about your work through your paper.

Bryn

I can't wait to share more work about their paper, and I certainly, honestly, I'm never gonna look at a game of Snakes and Ladders the same way again!

Resources

Developing a Canadian evaluation framework for patient and public engagement in research: study protocol. (L’Espérance et al., 2021)

The capacity for patient engagement: What patient experiences tell us about what lies ahead. (Canfield, 2018)

Let's help make patient engagement in research the standard or As PER Usual.