S2E7 - Engaging with your health data (Interactive Transcript)

In conversation with the SPOR Data Platform

Episode Overview

In this episode of asPERusual, host Anna Chudyk sits down with representatives from the SPOR Canadian Data Platform to learn about the different ways the network is engaging Canadians in conversations about their health data. Key topics covered include:

the ways in which multi-regional data access contributes to a learning health system,

how health data can contribute to improvements in health and health equity,

ways in which the network engages Canadians in conversation about what they think about health data and its use and the types of health data and outcomes that matter to them, and

patient and public engagement in the network’s governance.

Guests Kim McGrail, Frank Gavin, and Catherine Street also discuss key issues that patients and the public have raised about their health data, which revolve around the themes of:

trust, security, and safety;

equity, fairness, and access;

data availability and the types of data that are collected;

the language used to talk about data, and;

ownership — e.g., who owns health data? who controls how “their” health data are used?

As you’ll see in the episode, “Health data really is for all of us… so for those who are interested, there's ways to get involved. And those who are less interested can have some trust that there are people like them who are involved, and therefore they they can worry about other things that might be more of a priority and interest to them… we all have a responsibility to understand the data that we're using.” So what are you waiting for? Tune in and join the conversation about your health data!

Meet our guests

Catherine Street is the Director of the Newfoundland and Labrador SPOR SUPPORT Unit and the Executive Lead for Public Engagement with Health Data Research Network Canada. She has worked in Patient / Public Oriented Research since 2014, when she was appointed Director, NL SUPPORT at Memorial University, St John’s Newfoundland and Labrador .

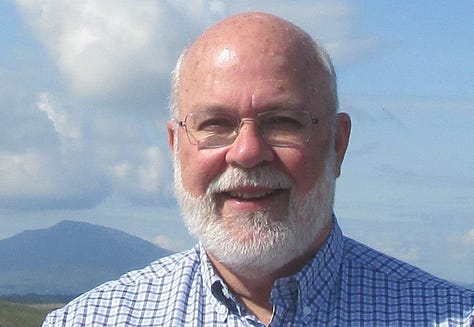

Frank Gavin chaired the Public Advisory Council of the Health Data Research Network (Canada) from 2019 to early 2024. He has been involved in healthcare and health research as a patient, a caregiver, and a member of the public, often in relation to children's health, since 1995. Frank taught English at Centennial College in Toronto for 30 years.

Kim McGrail is a Professor in the UBC School of Population and Public Health and Scientific Director of Health Data Research Network Canada. Some of her research uses large data sets to look at the effects of big policy changes such as changes in the way physicians are paid. She also has led deliberations with the public on how health data can be used to benefit people and communities.

Contact the host: Anna M. Chudyk - anna.asperusual@gmail.com

Table of Contents

How does the SPOR Data Platform impact Canadian Health Research?

How does the SPOR Data Platform raise the bar for health research?

Resources

All of the resources below are free for everyone to read:

Consensus Statement on Public Involvement and Engagement with Data-Intensive Health Research

The Conversation Canada: How can health data be used for public benefit? 3 uses that people agree on

The Conversation Canada: The public needs to know why health data are used without consent

Healthy Debate Article: Patients ’R Us: But do we have to be all the time?

Healthy Debate Article: The risks of equating ‘lived experience’ with patient expertise

Episode Transcript

Anna

Hi everyone. Welcome to season two, episode seven of As per Usual, a podcast for practical patient engagement. My name is Anna Chudyk and I am your host. As those of you who are familiar with the podcast know, this season we are focusing on bringing awareness to entities and networks that are funded by the Strategy for Patient Oriented Research, or SPOR for short. In case you're unfamiliar, SPOR is a national coalition that was created by Canada's major public funder of health research, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, to champion and support research that focuses on patient and public identified priorities and outcomes, and engages patients and the public as members of the research team. So with me today, I have Kim McGrail, Catherine Street and Frank Gavin from the SPOR Canadian Data Platform. Thanks so much for coming on to the show.

Could you please tell the listeners a little bit about yourselves?

Kim

I'm Kim McGrail, and I am a professor in the School of Population and Public Health at the University of British Columbia, and so I'm based in Vancouver. My background and training is in health services and policy research, but kind of at the intersection of of that plus health economics and social determinants of health. And I am a quantitative researcher. So I've always used a lot of data for my research. And that's how I got involved and interested in these kinds of data infrastructure that we'll be talking about today.

Catherine

I'm Catherine Street, I'm the director of the Newfoundland and Labrador SPOR Support Unit. So I'm based in Saint John's, Newfoundland, and I've been in this role since 2014. My background is as a clinical pharmacist, but I moved into management and then into the field of academia as a manager in 2008. I was very fortunate in 2019 to join the SPOR Canadian Data Platform, also known as Health Data Research Network Canada, and in 2022 was asked to be the public engagement lead.

Frank

I'm Frank Gavin, I live in Toronto. Until very recently, I was the chair of the Public Advisory Council for the Health Data Research Network Canada and a member of the executive. I got involved with this project back, I suppose, in 2019, around the time it started and was involved with the application for the funding for the SPOR Canadian Data platform. But I'm not a data person, so I've been involved with health care, health research, and in particular mostly as a volunteer since 1995 when I got involved because of my son's health needs and health experiences at the hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. So for almost 30 years, I've been involved in various capacities with children's health. I was also involved with the Canadian Drug Expert Committee as a public member for six years, I was very involved with the Child Bright SPOR network, which is a network focused on children with brain based developmental disabilities and their families. I was for 30 years a community college English teacher here in Toronto, and that's me.

Anna

Welcome once again. Thanks so much for wanting to come on to the show.

So why don't we start off by having you provide an overview of what the SPOR data platform is, and perhaps how it relates to Health Research Data Network Canada?

Kim

I think that the simplest thing to start out with is that the SPOR Canadian Data Platform is one of the things that we're developing, and Health Data Research Network Canada are the people and organizations that are doing that. So one is the network and the other is the product that the network is working on. That's how those two fit together.

We responded to a call from CIHR. It was an open call for a network to put forward a proposal to build what they call the SPOR Canadian Data platform. So this is funded under that Strategy for Patient Oriented Research. And the rationale, as I understand it, for why this was included in the constellation of the other SPOR funded entities, is that part of the ambition with patient oriented research, and partner oriented research more generally, is to really push Canadian health care systems in the direction of being learning systems. And so one of the the fundamental pieces of a learning system is data and the ability to use data for improvement, for innovation, for evaluation. All of those things, whatever they might be. And so the data piece is something that CIHR wanted to build into the SPOR program. And then our focus specifically is on multi-regional data access. So we have very, very well developed data systems and data centres in different parts of the country. But they are distinct and have operated independently. And so this is the first time that our network has the opportunity to more formally engage and work together as a network across the country, bringing all those together. So we have member organizations from every province, from two of the territories. We're working on bringing the third territory in, and also two pan-Canadian organizations with the Canadian Institute for Health Information, or CIHI, and Statistics Canada.

I know that many patients and researchers are really excited about the concept of multi-jurisdictional linkages of population level data sets. How do you feel that the SPOR data platform is supporting, and can be a game changer for patient outcomes and Canadian health research?

Frank

When I was involved very much with children's health, we got families together from different parts of the country. We realized very quickly that people had very different experiences, very different resources that were available to them, very different situations that we also had differences in, for example, what sort of things were funded and how they were funded and how they how services were organized. In some cases, we had people actually moving from one province to another because they understood that their child would receive different services that they wanted or perhaps couldn't afford in a particular province. So that's one thing.

I think people are naturally curious. People are curious about the fact that waiting lists, for example, seem to vary quite a bit across the country. You know, why is that? And is that a fact? Is it simply a rumour? Can we learn from what people elsewhere are doing and doing well? So these are some of the questions.

This interest in what's happening elsewhere arises quite naturally out of people's experiences. So and I think clearly getting data from different places can help people answer those questions.

Catherine

And I’ll just add to that, that in answering those questions, by using multi-jurisdictional research done through the Canadian Data Platform, we can ensure that those patients or families are comparing apples with apples and not apples with pears. I think that's a key point. A key advantage of HDRN is it ensures that comparison is of the same thing.

Kim

I think what I would add is that the vision that we have for our network is that health data will be used to improve health and health equity. And so the combination of, as Catherine and Frank have said about the learning we can do across the country, but also that focus on equity. The data world as it is changing so quickly with so many more different kinds of data that can be brought together. We have a large number of data sets that can be linked within provinces and sometimes across the country. And as we do more with data, I think we have an even greater obligation to make sure that we're doing things that are helping address inequities, that are supporting communities, that are certainly not going to be making things worse. So there's a strong commitment in our network to principles of inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility, as well as supporting Indigenous data sovereignty. And I think a lot of those things that we see as being those important principles, then also need to be informed by, we would say, public as well as patient family voices to make sure that we're using data in a way that actually is consistent with the principles that we say we have.

Frank

Another area that I'm familiar with is the way cancer drugs are funded, especially when you're an outpatient. So those drugs are funded very differently from province to province. And I know this is a particular concern of patients especially when they're outpatients that the different ways they're funded no doubt has some bearing on who can afford them, how people use them, etc.. And I know there's great interest among those patients and their families in how things vary across the country and what the actual effect is. So this is another area of health equity where depending on which province you live in, will determine whether you have to pay out of pocket certain amounts of money at a time when maybe you're under very special kinds of stress.

Catherine

I'd also add to what Frank has said, that it's not just the payment out of pocket, it's also the time to access the services differs within different provinces. Particularly at the moment with the pressures on the whole of the healthcare system from primary care right through to acute and tertiary care.

So what do you see as the network’s role and perhaps maybe some tangible activities that it's been engaging in to help ensure that there is more equitable access for Canadians to health care?

Kim

So that's an interesting question, and maybe I'll answer it in part by saying that's not really our job. This is where our network and what we've been asked to do under the Strategy for Patient Oriented Research is perhaps quite different from some of the other networks. We do not have a research agenda of our own within Health Data Research Network Canada. We're really very much supporting other researchers who want to use multi-regional data to do their research. So this is very much more of an infrastructure building thing, which has actually been quite interesting even from thinking about our commitments to public involvement. But what does that mean? It's such a different - I think Frank can say more about this — but such a different experience for people who we are engaging with because it's not about a particular research project or a tangible question. It's really about this whole data space in general and what do we think about health data and how they should be used. So we have a public advisory council, Catherine can talk about the work of the Public Engagement Working group, but it's very much topics that are more general and transferable across research projects than specific research questions.

Frank

I certainly think, you know, having been involved with a SPOR chronic disease network, Child Bright, where the connection between what patients and families are advising and particular projects is much clearer. So to give one example, within Child Bright, the network collaborated with some First Nations communities in Ontario to find out what was important to them. And what we heard back was that they had an issue - neonatal abstinence syndrome, which is about children who are born to mothers who are opioid dependent. And this has a real effect, and this was important to them. So this became one of our research projects. So then the work was done.

It's not like that in our data network. The public advisory council, for example, doesn't say there should be a research project in this area and we want people to do it. It's a more indirect process. But I do think we are part of a larger wave, if you will, or a movement where I think the key is around priorities, the kinds of questions, the kinds of issues. Can we set up mechanisms where there are opportunities for the public and for patient groups to influence how things are done, what they're done at different levels? So can we influence the different members of the Health Data Research Network Canada to think a little differently about how they choose projects and what they put their emphasis on?

So years ago, I heard about a project that was done from what's called the James Lind Alliance, which is a process begun in the UK, where they try to identify things that need investigation that haven't been investigated for one reason or another. And the outcome was that for people who have chronic kidney disease undergoing dialysis, that itch was a big, big problem to those people - to those patients. But nonetheless, there was absolutely no research practically done on it. And it really was a problem that affected whether people continued with dialysis or discontinued it or how this was a really important thing. But it was only by talking to a variety of patients and clinicians that this was surfacing. So I do think sometimes, you know, if we can bring a bit of humility to the process and make sure that people - sometimes researchers assume they know what's important, what's a value, what's what are the priorities of patients and the public. And if we can help influence this whole culture, if you will, to say, maybe we actually need to do some listening carefully to figure out what's important and then to influence what kind of data are collected.

If I could use another couple of examples. When I was with the Canadian Drug Expert Committee, we would often read these clinical reports and pharmacoeconomic reports. Those are very technical terms and the material was often very technical. But one thing I noticed, for example, was when people talked about the money that health systems spend, when we looked at the economics of health care, people could sometimes identify down to the nickel, how much certain procedures cost the health care system. But what they hadn't a clue how much the users, patients, families, etc. were paying, and paying in different ways: lost work, lost school time, distance traveled, hotel expenses. There's all sorts of information, data, if you will, that was never collected. And so hence part of whatever economic analysis you do is going to be distorted in some ways - impartial. So this is the kind of thing that has certainly interested me. Can we change this a little bit? And even some things, multiple sclerosis patient groups would tell us what was really important to them was whether they could live on two floors, whether they could manage stairs. But we had no data about patients being able to live on two floors, but this was really important to them. Instead, we had results from what's called the six minute walk test, which is a validated test which is useful but which is inadequate, certainly from the perspective of the patients.

So there are new kinds of data. There are there are problems, there are issues, there are needs that we haven’t adequately identified. And once we do, then we have to ask the question, okay, how can can we acquire the data? How can we do that? And I think this is an area where a lot of patients and members of the public are very interested.

Catherine

And that fits in nicely into some work that we've done through the Public Engagement Working Group for the Public Health Agency of Canada, in relation to what's referred to as the social license for users and users of health data. So Frank has talked about what we can use data for and how we can use data, but we also have to consider what the public are happy with us using data for. Are they happy with researchers using their anonymized or de-identified healthcare data for academic research studies? Most likely, yes. But are they happy or comfortable with their data being used for a big pharmaceutical company or another company to make a profit from the use of that data? Probably no.

So we've done a study on that to determine what people's views are on the uses of data. And interestingly, we're going to compare and contrast the work done here in Canada where we spoke to patients and the members of the public who had been involved in research, knew a little bit about patient engagement, patient oriented research, and compare and contrast that to studies that have been done in Australia through the Population Health Research Network, where they actually consulted with people who weren't involved in the health care system or weren't involved in academia. And we're just going to look at how the results varied. That will be coming up in June.

Anna

I'll be sure to keep a lookout for that study and to also post it on our website once it comes out. So for sure, keep me informed.

Catherine

It's actually going to be two separate webinars. So the webinar run for the Australian, a contingent and then two weeks later a webinar, repeated, run for the Canadian contingent. And then an interactive whiteboard for the two audiences to really spark off each other, send comments and just discuss the topic further. And from that discussion, we will determine whether or not we can take this research further and look at what other work we can do, comparing and contrasting to large countries.

Anna

And that's really interesting because I saw on your website for the HDRN that you offer a lot of different webinars as well, but it's also really nice as a patient oriented researcher, to hear that you're also using the webinar as a basically a new-age medium in order to solicit feedback from others who are engaged and to help you decide whether to move an idea forward. I'd love to hear about more of the patient centred initiatives that you guys have, but maybe before we do that

Why don't we take a little bit of a step back and ground the listener in the different patient engagement initiatives that you have built into your governance?

I know that there's a patient engagement committee. So could you tell us a bit more about that? And then it looked like you also had two other platforms that were really centred around eliciting the input of patients and the public or other stakeholders.

Kim

For the work of HDRN, we're very clear that we use the phrase public rather than patient. Now, I know that the Canadian Institutes of Health Research called SPOR the Strategy for Patient Oriented Research. However, a number of people who have had experience or even ongoing experience of the healthcare system don't consider themselves patients. They're members of the public. They're citizens. So it was a little bit before my time, but there was a conscious decision to use the phrase “public”.

We have a public engagement working group, which I'm the chair of, and that really brings together representatives from across the country to talk about how we may take forward public engagement within the work of HDRN Canada. Those representatives, some come from sites within HDRN Canada, others come from other support units. So again, under the Strategy for Patient Oriented Research, and others that actually come from healthcare providers. So we use it as a sounding board to learn and also to determine how we take forward other areas of work that engage the public, such as the social license work that I just talked about and some work on health data literacy, and also something I'm sure we'll want to talk about further on today, the Public Forum on Health Data for All of Us. So that's the Public Engagement Working Group. And the Public Engagement Working Group supports the Public Advisory Council, which Frank was until very recently the chair of. So I'll hand it over to Frank to give an overview of the Public Advisory Council.

Frank

Yes, the Public Advisory Council. We actually began with an interim council at the very start. We brought together half a dozen people or so, most of whom had in fact been involved with SPOR in different provinces, and we used their experiences. Most of the SPOR entities had started before we had. So we had the advantage of being able to learn from their experience.

We thought about what the appropriate council size was. We decided that 12 to 15 members was about right. That's very difficult when you have members from across the country, when you want a a group that, to the extent possible, reflects the variety, the diversity of Canada. You want people from different regions, you want people from rural and urban areas. You want people from different kinds of backgrounds. You want people with different kinds of health care experiences. In our case, we wanted some people whose first language was French. We wanted to have at least a couple of people who were were Indigenous. So the interim group thought carefully about the size of the group, the composition of the group, the kind of the mandate and roles that they could play. And when you have people with a very real diversity of experiences, you can't presume they're all going to have the same priorities. So we bring people together and talk about what's important to them, which would seem to be the shared priorities.

And I think some of these issues, what we have identified were, to a large degree, issues related to trust keep coming up in one way or another. Health data does not exist in isolation. You know, people hear about data and data breaches and all kinds of other areas. That understandably increases people's anxiety about the security, the safety of their of their data.

Lots of people are concerned around issues related to justice, fairness, and access. People are aware that there are problems related to access to the health care system, access to particular services. So how can we use data, first of all, to understand those problems and then to help solve some of them perhaps?

So we are discovering that there are certain large topics or issues that are are important to very many people. The way they approach them may be different. And I do think that we can't probably under emphasize the degree to which the experience of COVID has affected this. Maybe people are aware of the things that we didn't know, for example, we didn't know how particular populations were being affected by COVID. So we heard from other places that they had data around how different communities, different subpopulations or populations, different groups, you know, identified racial groups or racialized groups, how they were affected differently. And sometimes we couldn't even answer those questions because the data weren't there. Now, collecting that data is complicated, and people are understanding that.

But the other thing I would say is this, what we are learning more and more is that the world of data, the professional world of data, like other particular worlds, has its own language, its own vocabulary, its own way of talking. And that's often not understandable to people in the public. But we are trying as much as possible to make sure that this world, which actually has a big impact and a great potential impact on people's day to day lives, that it can be penetrated and that there can be some back and forth where people are actually speaking the same language. So our members of the Public Advisory Council have been quite preoccupied by saying, whether it's our own website, or the materials we use, or the materials our member organizations use, or how people talk about data. And even I would say as simple as as the word “data” itself, what does data mean? What what constitutes data? Some people think it's just numbers. But how can experiences be captured in data in some ways that are not simply converted into numbers? I don't know about this, but the more I hear about it, the more feelings, emotions, frustrations and so forth. How can we represent that as something that maybe gets incorporated into something called data. Or even the term “health data”. What's health data? Someone once said, the reality of it is, health data is only about data from health care institutions? Can individuals provide health data? These are all other questions.

Catherine

Thanks for that, Frank. In addition to the Public Advisory Council, you asked about how the public are involved in the governance and workings of HDRN or SPOR CDP. The chair of the Public Advisory Council also sits on the executive committee that meets every two weeks. And the chair of the Public Advisory Council is also invited to what we used to refer to as the “leads meeting”, which was when the leads from each of the sites would come together and where each of the working groups would come together. That used to meet monthly, but we've now split that site slightly into a leads and a site specific. So a lead from sites and a lead from working groups. So two specific, two separate meetings. And the chair of the Public Advisory Council joins the working group specific meeting.

So that's quite difficult to explain without waving my hands around or or having a diagram, but suffice to say that the chair of the Public Advisory Council is very much engaged in the governance and management of Health Data Research Network Canada. Kim, I'm not sure about the makeup of the board. There's not specifically a public representative on that, or is there?

Kim

We do have a board of directors because we incorporated it as not for profit, federal not for profit, in early 2020. And we have a competency matrix for our board, which includes people who have some experience with public engagement. So it could be that they have been a public engagement person on a research project, but it also could be a more professional aspect of that. We haven't really delved down into that, but for sure we have board members who were interested in becoming board members in part because of their experience themselves, or have a loved one through the health care system.

In fact, what I see is that that's what draws a lot of people into the health sphere is some kind of personal experience, and that's for people who are engaged from the public or as patient partners. It also informs research directions that faculty members take. It informs some people's decision to go into medicine or to some kind of health provider role, so that it's all those kinds of different, all the different angles that people bring to this and that, you know, in our intersectional experience, is all layered in there. But we are very conscious of that being something that we pay attention to specifically and deliberately in conversations.

Anna

I'm glad you also brought up that point, Catherine, about how representatives from the public committees are integrated and meet with the other committees as well. Something that we covered in season one, and I've also had people share with me and experienced it myself, is that a committee can't be very effective if they don't have any link to the decision makers within an organization. Or even more importantly, they should actually have decision makers within the committees as well, so that they're not actually just spinning their wheels in the mud, but that whatever they come up with gains traction because there's that force within it to actually affect change. I'm really glad to hear that's the structure.

Something that I was wondering is it seems like there's a lot of opportunities for coming up with ideas and priorities and really critically engaging with the idea of data and how data can be used to better outcomes of patients and the public, as well as also in research.

Could you help us better understand some of the tangible initiatives that your platform has right now, and how perhaps the listeners, or just any public members they know could get involved in them?

Catherine

Do you mind if I start with the public forum? Because I think that's the most obvious one at the moment. Earlier on, I mentioned that the the Public Advisory Council and the Public Engagement Working Group had taken a lead on organizing a public forum. It was our first one last year. It's referred to as Health Data for All of Us. And last year the focus was on sharing ideas and priorities. So that is a forum that is open to anybody to attend. It's a hybrid format so people can attend in person or online. And last year it was a selection of panel discussions and presentations. Some of the key findings that came out of last year's forum related to the points that Frank mentioned regarding trust and transparency. And we're taking those findings into this year's forum, which will be on the 23rd of April in Montreal. And the title of this year's forum is again “Health Data for All of Us”, but with the added line of “Earning Trust Through Transparency”.

The opening plenary by Antoine Boivin, who is based within Montreal. He has huge experience in terms of public and patient oriented research. And he is being joined by a community member to share their experiences working within Montreal. We then have Harlan Pruden talking about indigenous data sovereignty, and we're keeping that as a standalone session just to highlight the importance of Indigenous data sovereignty to the work of the Health Data Research Network. We have Kim and Alies Maybee presenting in relation to the Pan-Canadian Health Data Strategy and the findings of the Expert Advisory Group. I believe specifically Kim, in relation to how data is managed within provinces and how we'd like it to be managed. Is that correct?

Kim

And tying to the ideas of the pan-Canadian Health Data Strategy put forward on around a public assembly and that sort of ongoing engagement.

Catherine

We also have set up sessions, concurrent sessions regarding inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility in the use of data. A presentation from Bree at the University of Sherbrooke and a final plenary panel in relation to artificial intelligence. As Frank has mentioned, artificial intelligence is a concern of a number of the Public Advisory Council members, and what artificial intelligence may mean for health data and the safety and security of health data. So bringing together a panel of individuals who are experienced of working within the field of artificial intelligence to have those discussions about its uses within health. So registration is open for the forum. I'm not sure of the date that the podcast will be going out Anna, so hopefully if it's before April the 23rd, people may register. Alternatively, if it's after, recordings will be up on the HRDN website.

Anna

And then something that I'm going to ask next is and I wasn't even very clear on it from the site. Like I saw that you guys have DASH, which sounds like a great thing, and it's helping people be able to better request and manage multi-jurisdictional data. And then you also have what seems like forums for the public to come in and really share their ideas, but also, more importantly, critically engage with the concept of big data.

When all of this information comes in, is it within your purview as well to somehow help push this forward into other people's research agendas, since you don't fund research, or how does that aspect work?

Catherine

The advice that we get from the public would be be informing your discussions say, when you're on the expert advisory group, and your discussions with CIHI and other federal agencies.

Kim

It's such a it's such a good question. All of this informs things, but we just don't have the right tools to be pushing. What we're trying to do right now is to make sure that people are thinking about certain things when they're putting proposals forward. So I hope it's almost a silly example at this point, but we wouldn't really like to see a trial that only includes men without women, or without the ability to disaggregate data and other important ways and that sort of thing. Certainly, if you're doing research that involves Indigenous communities, we would expect to see some kind of engagement with those communities. There's lots of ways that we would like to encourage people, but I think this is where it gets similar to other SPOR entities, we don't have the ability to make requirements. People already have the requirements that our data governors set in all our multi-jurisdictional research. It's not our job to add to that, but we are trying to raise the bar a bit and help people think about data in a different way.

So in addition to what Catherine was describing with the public forum, which is very clearly a product of a lot of work of our Public Advisory Council, plus the Public Engagement Working group, we also have this series of what we're calling “Big Ideas for Health Data”. Which is really trying to draw out inclusion, diversity, equity and accessibility in data and really reflecting a lot of the conversations that happened or started during COVID around race based data and disability data and gender and gender identity within data, and how we need to change our classification systems when we're collecting data. But also how we need to think about both being mindful of research when we're using those data, how we report it, how we do intersectionality research. Like in the way that Greta Bauer talks about it, all of those things. So that resource is aimed to some degree at researchers, but we hope that all of that is accessible and of interest to the public as well, because it informs the way that we're thinking very differently about quantitative data and our responsibilities around the use of quantitative data, certainly different from when I was trained in this area.

So is it fair to say that one of your big roles is to really help people critically engage with the concept of data, how it's used, analyzed, managed, and to bring the public into these conversations as well?

Frank

Yes, I think the network has a particular strength in that it has it has lots of partners. It has lots of connections. So there are many different organizations that are part of the network, but the network is also connected to the other SPOR entities, for example. So I think there are issues that sometimes, within certain spheres people may make a certain assumptions. For example, this question around when they talk about data, whose data is it? We often hear from patient groups, for example, and patients the phrase “my data”. And they often have certain notions. And it's important to them what they think of what's included by that term “my data”.

And there are legal issues around who actually owns the data there, but also the question of control, so that when you go into a hospital, what data related to you is something that is collected routinely, entered into larger bodies of data, etc.. What data can you decide goes where? I think there's an awful lot of mystery in many people about this. So I certainly think we need a lot more clarity. And where there's not transparency, that's where you get fear, that's where you can get mistaken notions. So what actually happens? I think there's a great need there. I think in my experience with patient groups, even the issues of what can I say yes to? What can I say no to? What kind of data related to my experience in the healthcare system is going to be collected whether I give permission or not? How is it used? How is it not used? All of these things, I think in many cases sometimes there's even some element of urgency to making clear, to becoming more transparent, sometimes not just with information but with explanations. Here's what we're doing, here's why we're doing this.

So it's really a matter of also connecting the dots. So what do you do with this data? Is that something people have questions about? So I think it's important to say, and maybe they have fears about this as well. Can we help all the people involved in collecting, storing and using data become more mindful of the need to make what they're doing understandable to people. In fact, you need to do this if you're going to maintain people's trust. It's possible that there could be restrictions put on the use of data that would very much hamper certain kinds of research, certain kinds of improvements to our health care system if the if the level of trust sinks so low that we that we have to put in truly draconian measures. But the public needs to be satisfied that the people collecting, storing and using their data are in fact trustworthy. So show us this, make the case for this. Tell us why what I fear happening is not going to happen, or what you're doing to try to prevent that in in language that I can understand.

Catherine

That was an important point there as well. It's about us proving that we are trustworthy rather than getting somebody to trust us. The onus is on us making the change, the data holders, that we are trustworthy.

Anna

Thanks Frank and Catherine, I really appreciate how you're able to put these big ideas forward, but then also ground them in personal experiences that I'm sure that everybody out there listening to can relate to.

What would you say to someone who's very, very interested now, they share these same concerns, or maybe they have ideas that they'd also like to put forth… What are ways that the public and researchers could get involved?

Catherine

Well, I'll talk specifically about the public. The public advisory council members have a term that they serve. And in about May of each year, we check in with each of the public advisory council members whose terms are coming up as to whether they wish to renew. There is a limit on the total length that people can renew for, or whether they wish to step down. Over the last few years people have have stepped down. So we have done a recruitment call which goes out through our social media channels, and it's also shared through the communication channels of associated organizations like the support units, Child-BRIGHT, one of the chronic disease networks. So that call will, as I say, probably be going out again in May and we will be looking for probably at least two, maybe more new members to join the Public Advisory Council.

Frank

We've also had certain projects, like the question around social license that have involved people who are not members, you know, people from patient groups, members of the public who are not members of our council.

Anna

Is there anything else that you'd like to share with our listeners that perhaps we haven't had a chance to cover today?

Kim

I think I'd like to pick up a little bit on the idea of public deliberations. I've done a couple of these myself as a researcher and these are large scale (as in time), large scale, small group, or sessions where you can get very deep into very particular kinds of topics. So the deliberations that I've been involved in have had to do with data, data linkage, data sharing and inclusion of private and public sectors’ sources of data in these things. And so what you do in these deliberations is try to recruit a cross section of people and not a systematic representative representation of the population, but more to maximize the diversity in the audience.

It's usually around 30 people in the particular form of deliberations that I've done, and you work in small group sessions over four days across two weekends. So we use weekends so that you can include as many people as possible who might be working and might have other commitments. And then it's two weeks apart. So you've got a weekend a couple of weeks away where you go back to your community and you can talk with everybody that you want to about what you've heard and learned, and then you come back again and try to make some policy recommendations.

So deliberations are really, really useful for areas of consideration where there's trade offs, where there are norms and values involved. So we're not going to deliberate on an economic model. An economic model is an economic model. But we're going to talk about how our values might inform, in this case, the way that we want to organize and use data. And they're really, really useful for topics that are just complex enough that you're not going to get a good answer from a focus group, but more specifically from a survey, because you can't even really craft a question like, “do you want your data to be used for health research”? Well, I'm sure the answer is “yes, but only if context dependent, if these guardrails are in place”, all that sort of thing.

So when we do these, we only do them when we have a policy receptor. Somebody who is wanting this information and is going to take the policy recommendations seriously. And we allow them to observe so that they can see the process that the public members go through. And and it's really powerful, because what people come to realize who are not inclined this way is that you can bring together a group of people who don't know each other, who are very diverse, who come from different parts of the province or different parts of the country, and give them enough information to have a deliberative conversation. And they come to some really, really powerful policy recommendations, a very effective means of doing things. And I think I agree with Frank, that the world we're working in, in the data space, with all of the changes happening with artificial intelligence and all of these other things, it's a very ripe area for having these kinds of deliberative conversations, which then can feed into practices that will increase the trustworthiness that we're looking for in the systems that we're operating. And there's lots more that we could say about that, but I think I'll just leave that there for now.

Catherine

The other area I would like to highlight is the importance of health data literacy. That's in relation to the public. So the public understanding what we're talking about when we talk about health data. So ensuring there's no ambiguity there. And the need for researchers working in the field of health data to really have an understanding of what the words mean as well. So ensure we are talking about the same things when we think we're talking about the same things. So that is an area of work that we're just moving into now. And just to say watch this space in relation to health data literacy.

Frank

And I would just like to point out that there's a paradox that, you know, clearly more data is being collected and more kinds of data are being collected. And it's easier to collect certain kinds of data. Now we have maybe data over abundance. Yet all this is making clear, I think, that there remain important data gaps. And I always find out from listening to people and sometimes reading what they say, if they're making submissions from different groups that gaps exist that I hadn't known about or had assumed were not gaps.

One of the things that has struck me is that as we accumulate more data, as you're aware that perhaps we have an overabundance of data or a great abundance of data, I'm not sure that you can ever have an overabundance of data, although the more data you have, sometimes the harder it is to choose which is the most important, which data you're paying attention to, which data gets regarded as as important. And not everyone, I think, agrees about what data are the most important. But there remain data gaps, and the more people you listen to and the greater variety of people you listen to, the more aware you can become that there are important gaps, at least for certain groups of people.

That needs to be recognized. And so for me, the communication skill always that's undervalued is the skill of being able to listen well. And I think everybody who's involved in the collection, storage and use of data really does need to become to become better listeners, to develop those skills, to know when to listen, to know to whom they should be listening. And I think that's part of what we are trying to do to make the system more attentive to what people are saying.

Kim

I think I just have I have to say one more thing, just based on hearing all of that. And and that is there's this wonderful book called Data Feminism that really touches on a lot of the things that we think about and are working through within within Health Data Research Network Canada. It's an open source book, so it's freely available online, and it's written in a very, I would say, captivating kind of style, very accessible. And one of the things that they talk about in that book is the work of this artist named Mimi Onuoha, who has developed what she called the library of missing data sets. And I think this speaks to something Frank was talking about. We can have all of this abundance of data, but we still may not be collecting the things we actually need to understand what's most important to the public, to patients, to family members who are encountering certain things within the health system, and being really conscious of what we're leaving out when we're collecting data can be just as important as focusing on what we have in front of us to use, because it's actually been collected.

Anna

Thanks so much for mentioning the book. As soon as I log off, I'm going to Google to see if hopefully it's also available as an audiobook so that I can read it when I'm driving or putting the dishes away and so forth. And I'll also be sure to include a link to the book on our website as well. For anybody out there that's listening but didn't get a chance to note its name. And so, Frank, it's like you read my mind in terms of what my final question was going to be. And that is:

What would you say is a key take home message that you want the listeners out there to be able to take from all that you've shared with us and apply to their own work?

Anna

And I know that's a huge question. So maybe not from all that they've listened to, but definitely the main take home points that you'd like people to internalize, but then also, importantly, apply to their own patient oriented research.

Frank

I would say that in my experience in different areas of health and health research, societal values are often invoked or referred to, but they're not always well understood, and they're not even always well identified. And if in this process we can actually identify and have people talk about what are the values that are shared and how can these inform the health system and the health research system? That's something which I think would be immensely beneficial.

Catherine

I would add the need to really listen and not to just listen to the loudest voices, to listen to the quieter ones, and to ensure that you engage as diverse a population as you can to get as wide ranging views as you can. And to remember that people don't always feel comfortable expressing their views in an oral way. Give people the opportunity to contact you through email, write to you, or to speak to you separately, away from a wider group, particularly some of the younger or newer members of a Public Engagement Working Group can feel very intimidated by some of the older, more experienced public and patient advisers. So make sure you listen to everybody.

Kim

And I would say that health data is really for all of us. As the title of our public forum suggests. That doesn't mean that it needs to become a full time job for all of us. But it does mean that for those who are interested, that there's ways to get involved, and for those who are less interested, that they can have some trust that there are people like them who are involved, and therefore they they can worry about other things that might be of a more priority and interest to them for whatever reason. I think we all have a responsibility to understand the data that we're using. It's not just neutral, agnostic data. It comes from some place, it's been imbued with power and decisions and classifications and leaves things out as well as it writes some things in. And we do need to understand that when we're using data. I think as a network, our hope is that data can be used to not just identify, but also to reduce inequities.

Frank

Maybe if I can add one more thing, that is my experience in the world of child health in particular, but in health in general, indicates that people do want not just want their problems identified, but they want their their strengths, their achievements also identified and recognized to give a whole picture of people's lives. And I think, you know, if we're only collecting data about community’s deficits or people's areas of weakness, we are risking doing a great deal of unintended damage. And so that so I think people, patients, families, communities really do want the whole of their experience captured and recognized.

Catherine

There are people behind that data, Frank.

Frank

Yeah.

Anna

I couldn't think of a better or more powerful parting words. Thanks so much to all of you for coming on to the podcast today, and for engaging me in such deep and thoughtful discussion. As we wrap, I'd like to remind the listener out there to please be sure to check out our website asperusual.substack.com, for resources from today's episode and interactive transcripts from this and previous episodes. While you're there, please be sure to subscribe to this podcast, or you can also do so wherever it is that you download your podcast episodes from. If you'd like to contact me, please shoot me an email at anna.asperusual@gmail.com. As always, thanks so much for tuning in. And until next time, let's be sure to keep working together to make patient engagement and research the standard or as per usual.