S3E2 Transcript - Patient Leadership, Indigenous Partnership, and Capacity Bridging in Kidney Research: A Can-SOLVE CKD Deep Dive

Overview

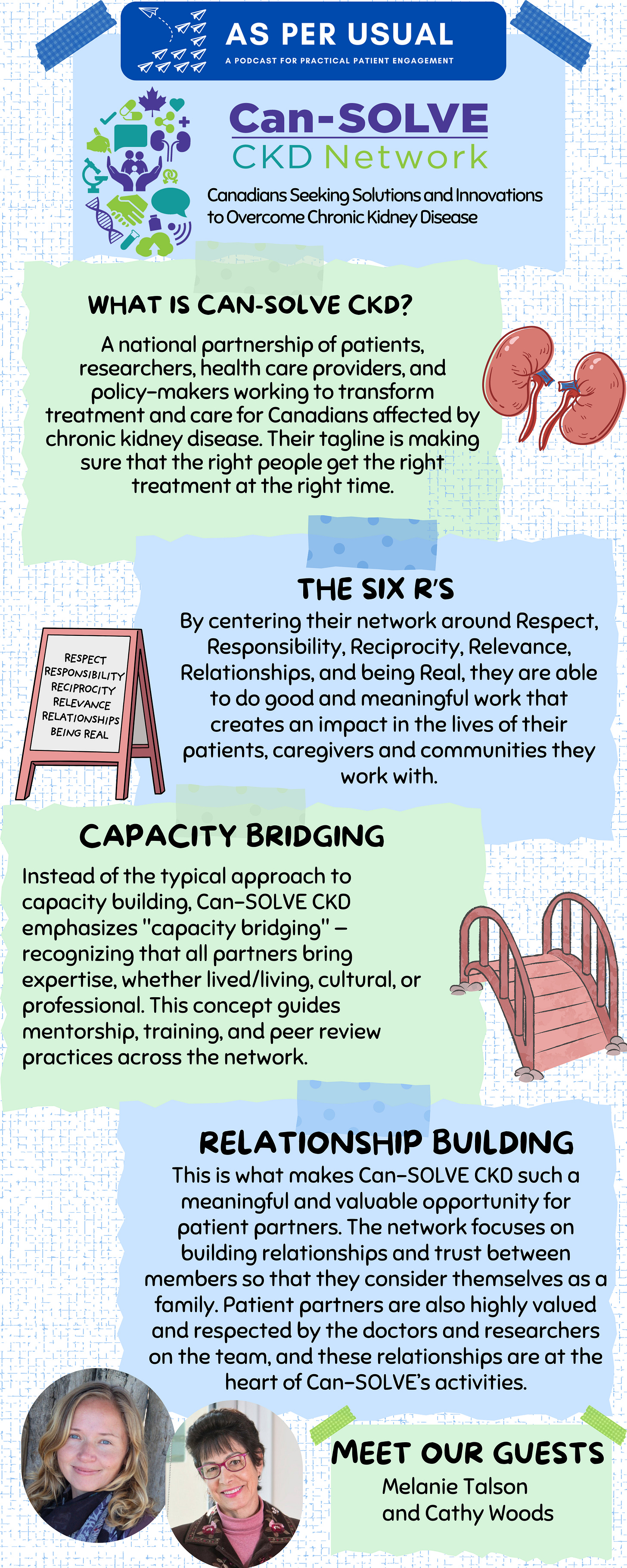

In this episode of asPERusual, host Anna Chudyk sits down with Melanie Talson and Cathy Woods from the Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcome Chronic Kidney Disease (Can-SOLVE CKD). Key discussion topics include:

Patient Leadership at the Heart of Research

Can-SOLVE CKD is a pan-Canadian, SPOR-funded network driven by patient voices — especially through its Patient Governance Council and Indigenous Peoples’ Engagement and Research Council (IPERC) . Patient partners co-lead projects, shape research priorities, and ensure meaningful engagement at every stage.Transformational Approaches to Engagement

The network is built on the Six R’s of engagement — Respect, Responsibility, Reciprocity, Relevance, Relationships, and Realness — creating a culture of trust, collaboration, and safety for all partners involved. Their approach prioritizes consensus, inclusion, and shared leadership.Capacity Bridging, Not Building

Rather than viewing patient partners as blank slates, Can-SOLVE emphasizes "capacity bridging" — recognizing that all partners bring expertise, whether lived/living, cultural, or professional. This concept guides mentorship, training, and peer review practices across the network.Lasting Impact and Mutual Empowerment

From screening initiatives in Indigenous communities to research projects reshaped by patient input, the network is seeing real-world impacts. Equally powerful is how patient partners like Cathy describe their involvement as healing, empowering, and deeply purposeful — creating space for ordinary people to do extraordinary work.

Meet our guests

Melanie Talson, MA, is a medical anthropologist with a background in qualitative research, patient engagement, co-operative inquiry and participatory action research. Melanie supports patient engagement in research as the Can-SOLVE CKD Patient Partnerships and Capacity Building Manager. Believing in the critical importance of conducting research ‘with people not on people’, Melanie maintains a strong emphasis on relationship-building, valuing the expertise patients bring to the research and recognizing patient partners as co-creators of knowledge every step of the way.

Cathy Woods is a proud member of Naicatchewenin First Nation in Northwestern Ontario & now lives on Treaty One Territory in Winnipeg Manitoba. Her traditional name is Giwetashked Giniw Ikewe (Circling Golden Eagle Woman) and she is a member of the Bear Clan. Cathy retired recently as an Indigenous Liaison Specialist.

Cathy has been involved as a patient partner with Can-SOLVE CKD since the network’s formation. She is the patient partner lead of the Kidney Check research project, which seeks to screen, triage, and treat Indigenous people living in rural and remote communities across Manitoba, Alberta, Saskatchewan and British Columbia.

Cathy also served as a founding co-chair of the Can-SOLVE CKD Patient Governance Council and the Indigenous Peoples’ Engagement and Research Council (IPERC). For the past few years Cathy is the co-chair of IPERC and serves on many other committees within the network as well as the Leadership team.

Cathy views her journey of kidney disease as her chance to give back to her community and to those who assisted her in dealing with her disease.

(Na-catch-che-way-win)

Contact the host: Anna M. Chudyk - anna.asperusual@gmail.com

Table of Contents

Patient Partner Involvement in Peer Review and Project Review

Can-SOLVE CKD Network Principles of Engagement and Capacity Bridging

Getting Involved in the Can-SOLVE CKD Network

Resources

All of the resources below are free for everyone to read:

Strategy for Patient Oriented Research (SPOR)’s website

Can-SOLVE-CKD network’s website

Transcript

Anna

Hi everyone. Thanks for tuning into season three, episode two of asPERusual, a podcast for practical patient engagement. My name is Anna Chudyk and I am your host. In the previous season, we focused on raising awareness for entities that are funded by the Strategy for Patient Oriented Research, or SPOR for short. In case you're unfamiliar, SPOR is a national coalition that was created by Canada's major public funder of health research, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, also known as CIHR, to champion and support research that focuses on patient and public identified priorities and outcomes, and engages patients and the public as members of the research team. Patients and the public who engage in this research team member capacity are often referred to as patient partners. We've dedicated the first two episodes of this season to featuring some of the SPOR funded entities that we did not cover in season two. Then we're switching gears to focus on engagement of youth and families. So now that we've gotten our housekeeping items out of the way, I'd like to introduce you to today's guests, Melanie Talson and Cathy Woods from Can-SOLVE-CKD network, a SPOR funded pan-Canadian network of patients, scientists, and health care professionals creating innovative kidney care solutions. Cathy and Melanie, thanks so much for coming on to today's episode.

Can you tell us a little bit about yourselves and who you are relative to Can-SOLVE-CKD?

Cathy

My name is Cathy Woods. My traditional name is Giwetashked Giniw Ikewe, which means Circling Golden Eagle Woman. I'm a member of Naicatchewenin First Nation in Ontario, and I've lived on treaty one territory in Winnipeg, Manitoba for the last 30 plus years.

I became involved in Can-SOLVE-CKD in 2016, but when I first got kidney disease, it was in 2010. I was diagnosed by my primary care physician and went on to see a specialist, and I was diagnosed and treated for membranous nephropathy. My treatment involved a lot of drugs and a lot of treatments. Through my treatment, I also use traditional ways of knowing and being and I worked with a group of Elders. I had gone to see a traditional healer and I had teas, I attended a lot of ceremonies. I had a whole group of Elders that I met with on a regular basis, and that that kept me uplifted and moving forward as I went through kidney disease. I was quite fortunate with my kidney disease that after aggressive treatments in January of 2013, I could say that my kidney disease had had left my body. I realized how fortunate I was through that process to be able to be well again.

I have talked to a lot of patients about this and families about as well, but one of the things about kidney disease is that when you find out that you have it, your first thought is “Oh, no, my kidneys are going to fail, and I'm going to die” and so that's one of the things that you often think about. I realized that I was very fortunate to have been diagnosed early, and that's why one of the projects that I'm working on is a kidney screening project in Indigenous communities, where we go to Indigenous communities and screen people for kidney disease.

I became involved in Can-SOLVE-CKD in 2016. I went to a meeting in Toronto where we were policymakers, there were doctors and researchers, patients, caregivers, donors. We had a lot of folks like that present in the room, and we worked on prioritizing the projects that were going to become the basis of Can-SOLVE phase one. We prioritized those projects with heavy patient involvement, and the researchers in the room listened to us. One of the things about patient involvement in research is that it improves patient outcomes, but it also improves the value of research, and it's more valuable to the patients to study things that are going to improve our quality of life. So that's one of the first basis of patient involvement that I was able to understand. And we encourage those that are interested in working with patients to work with patients from the very beginning, from even the very concept of figuring out the research question. We don't want to come into a project until we know that patients will be involved in the whole process and not just be involved in little bits of it.

I think the biggest thing that I had to, as a patient, understand about research is that it is a long process from the development of the question to actually putting the abstract together, the ethics. I mean, we all know ethics can take a long time to go through, and patients need to be involved in all of those aspects.

The last project we had was supposed to be five years, which turned into seven, then turned into eight because of Covid, and it's a long process in the implementation of the results of the project and the conclusions often don't take place for several years. The good thing about that is I've been involved for so long, since 2016, that I'm now able to see as patient partners, a lot of the suggestions and things that have been developed by our researchers being put into action in our kidney care clinics and by our nephrologists. So with that, I will pass it over to Melanie. Miigwech.

Melanie

Thank you Cathy, and thank you Anna for having us on your podcast today. I’m happy to be here and happy to share some of the good work that Can-SOLVE-CKD has been involved in, with the help of patient partners like Cathy. My name is Melanie Talson. I am joining you today from the Saanich Peninsula on the southern tip of Vancouver Island in British Columbia, which is home to the W̱SÁNEĆ peoples, and I just want to acknowledge the people who inhabited and took care of this land, who have been custodians of this land, and continue to live and thrive on this land since time immemorial, and I just want to acknowledge those peoples and this land with reverence and gratitude.

My current role with Can-SOLVE is as the patient partnerships and capacity building manager, and I've been in this role now for about a year and a half. Prior to that, I first got engaged with Can-SOLVE-CKD as a research coordinator in 2018 for a research project called the Triple I project, which was working to improve information, interactions, and individualization of hemodialysis care for patients across Canada. That research project was my first introduction to the network and I was really pleased to get involved because it had such a strong patient oriented lens and focus. From there, I continued to work as a research coordinator on the follow up project to that is called Mind the Gap, which identified that there was a real, missing piece in terms of mental health care needs and addressing mental health for patients receiving hemodialysis care. From there, I have moved into this current role, taking a little bit more of a focus around helping to engage patients in the research and also in capacity building and working on different strategies to support patient oriented research in the network and beyond. So I do work in knowledge dissemination and stuff like that.

I wanted to also mention just briefly that Can-SOLVE-CKD network is a network that consists of:

researchers

nephrologists

patient partners

multiple stakeholders who have an interest in kidney health research and patient oriented research

from across the country. And the acronym stands for Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcoming Chronic Kidney Disease. And as Cathy mentioned, the network was first established in 2016 with the patient voice at its core since its inception. As the network has developed and funded research projects from across the country, that patient voice has remained at the very heart of the network and all of the work that the network does. So I'm just pleased to be a part of it and to help further patient oriented research in Canada and internationally.

Anna

What is Can-SOLVE-CKD’s mission or role within our health and research ecosystems, and how does it go about achieving this mission?

Cathy

I think the first iteration of Can-SOLVE phase one, as we call it, had 18 research projects on it. The basic tag-line on that, which we actually still use in a lot of different circumstances, is making sure the right people get the right treatment at the right time. Each one of the research projects that was accepted into phase one talked about prevention or care or aftercare for families, and each one of those research projects fit into those categories. And then in phase two, which started in 2022, moved more into a knowledge mobilization. We are looking into how we can take everything that we've learned on these projects, and how can we mobilize and get this information and new innovations out to communities.

In terms of the way that we do things at Can-SOLVE — we have at the head of Can-SOLVE a steering committee, and I'm part of the leadership team. We meet weekly and go through everything on a regular basis. We also have a core team that are in different parts of Canada, and they oversee the work that is being done. And one of the things we do in terms of patient engagement is that we guide the nature of the work. Both the patient governance council and also IPERC (Indigenous Peoples’ Engagement and Research Council). Those are the two main governing bodies of Can-SOLVE that we work with. And within those, we also have many other committees. We have the paediatric committee, the steering committee, we have the rocket committee that oversee all of the various projects. We have a lot of different aspects that fit into it. But the basis of how and when we move forward is solely upon the guidance of the patient governance circle and the Indigenous Peoples’ Engagement and Research Council.

From my perspective, I was involved in both the founding committee for the patient governance circle. We have three executive members, myself, Mike McCormick in Toronto, and Kate Chong in BC. We operate probably a little different than what other patient orientated research projects do. We always have at least two patient partners on every committee, and quite often the patient partner is the co-chair of that committee. We usually have a patient co-chair and a non patient co-chair, whether it's a researcher or part of the core team. And so each one of our committees is like that, and we very much depend on each other.

One of the things that I've come to understand through the years, as a patient is I'm really fortunate that I've been well for over ten years. But we’re also working with patient who’ve had transplants, we deal with people who are on dialysis, we deal with a lot of people who are maybe not on dialysis, but on a lot of medications, all sorts of things. So we always have a backup in place all the time so that if someone gets sick or is unwell, then we have another and we all have worked on the same stuff, so we're all on the same plane and we know what we're talking about — you don't have to update them or do anything in terms of that. We've all been heavily involved in all of our committees, so we know how to move forward. And I'm really proud of our leadership team, because our leadership team is composed of our main principal investigator (PI) Dr. Adeera Levin, executive director Heather Harris, Dr. Malcolm King, Dr. Matt James, Dr. James Scholey and myself. We have two Indigenous representatives on the leadership team. For us at Can-SOLVE, it’s really important that we have that basis for how we move forward.

Anna

I think that's something really important for people to think about. We always talk about having at least two patient partners on any project for camaraderie, for partnership, to help shift the power dynamics between just having researchers or clinicians at the table. But very seldom have I also heard people mention the practical reason of having extra voices there as well, because you never know the nature of people's health conditions. And I'm sure that also helps alleviate some of the guilt that we always feel when we want to show up and be present. And now I'm talking about myself as a researcher, but also a person who has different health conditions, and you can as well. So that's really great.

I also thought it was really interesting, you mentioned before we started recording about the idea of peer review and project review and patient partner involvement in that. I was wondering whether you could please expand upon that for our listeners?

Melanie

Yeah, I can speak to that a bit. I'll just mention that we have, as Cathy has described, the Patient Governance Council and the Indigenous Peoples Engagement and Research Council, and both of those councils are really at the heart of the network. The Patient Governance Council currently has 12 members, and we have room for about 15. That way there's opportunity to have the backup of the backup, and if we need to call on people, we don't want to have to call on the same people all the time. But we do have this smaller group of a dozen or so participants who are pretty agile for helping to make decisions, to weigh in on different aspects of the network and the work we're doing. And one of the really important pieces that the patient governance council is involved in is project reviews. So currently we're in our phase two of the Can-SOLVE network research funding, and we are currently funding nine research projects. And those projects have a review and reporting process. And part of that is that a committee of reviewers will:

Peer review the project

Offer ways to strengthen and support the project

Provide advice

Provide accountability around the research.

Included in that committee are patient partners and members of the Indigenous Peoples Engagement and Research Council. Actually one of the co-leads of the rocket review committee is a member of the both the PGC (Patient Governance Council) and IPERC. So we have built into the review process input from the patients who are involved in that as well.

Once we have done the review process with the projects, we come back to provide sort of a check in with the projects. And these project “check-in calls” as they're referred to, is an opportunity to have the dialogue around that review. We also have members from the Patient Governance Council present to offer some sort of an asset based approach to improving, promoting, and supporting their patient engagement for each project. Each project will have very different needs around how to improve their patient engagement, but they also vary in the project's range both thematically and also pragmatically. Each project is quite different, and the way they engage patient partners is also different. So we have two, sometimes three, PGC members attending those project check-in calls.

Included in this, we've also built in a sort of mentorship program. So patient partners who have done this process before are paired up with a patient partner who is new to this process. We begin with a preparatory meeting to discuss the project, to go over the review committee recommendations, and to just get a snapshot in terms of where the project is at, what they're doing well, and how we can support them to do even better in terms of their patient engagement. And so when we go to those project checking calls, the PGC members are there to act as consultants on patient oriented research. So they're engaging with the research coordinators, the principal investigators, as well as the patient partners who are members of that research team. So it's a really great reflective process.

We had great success with this last year, we conduct these project check-ins right around now in the fall, and last fall the reflections that we received back from the projects were all really positive. And they found that having the patient partners there as part of this project check-in really supported the asset based, strength based approach to supporting the projects and also building in a bit of that accountability, and it was really helpful and beneficial to the project and the patient partners. It's a really great capacity building opportunity for getting to know the projects a little bit more intimately and getting involved in the research, looking at it through that lens but also being there to support the patient partners who are on those projects as well. So it's a great relationship building and collaborative effort to promote patient oriented research. We take all of that feedback back to the Patient Governance Council and have that dialogue around

how did that project check-in call go?

What how are they doing with their patient engagement?

How can we further support it?

So it's a really reflective, iterative process that I think is quite successful, and I think it's a nice way forward to building in that patient oriented lens in all the stages of a project.

Cathy

I also think it's really important for the researchers. I think the patients learn a lot through that process, but I also think that the researchers really learn a lot through that process because it's really helpful for them. We might ask tough questions about decision making, like where the patient’s involved in that process. Like “why didn't you ask the patients about what they thought could be a resolution to that?” I think the one thing that I can say through the patient check-in calls that I've worked on over the last couple of years, is that quite often, researchers are afraid to ask patients to do something. Whether it's a phone call or email, in terms of when they're gathering together or things are happening. And from my perspective, I wouldn't be involved as a patient partner if I wasn't interested in the whole process:

I want to know what the question is

I want to know how we can improve the question

I want to know what the process is

I want to know what the reporting is going to be

I want to know what is the outcome that we're doing

I've worked on different projects where we're not getting the information from the sources that are supposed to supply us the information. We've penned letters on that saying, as a patient partner I believe in this research, and it's really important to us as patient partners that this research proceed, but we cannot do it without “this, this and this”. Can you please make sure that we receive this in a timely fashion to be able to complete the project. And I also find that researchers are sometimes reluctant to ask the patients because they may not have the time or something. But it’s still important just to send us out an email saying this is what's going on. And I think that was more relevant and became more apparent during Covid when a lot of projects appeared to have stopped, but they didn't really stop. They continued on, but because of Covid, there wasn't a lot of reporting back to patients on what the problem was, why they couldn't proceed or do things. And so that whole issue of communication back to the patient partners, I've challenged each project that I've peer reviewed and said to them:

How about asking the patients about that?

How about doing those things differently?

How about making sure that once every four months you're sending out a newsletter to your patient partners?

You might have four patient partners, but only 1 or 2 really active, so why not send out a thing to the patient partner saying, this is where we're at, we're waiting for this, and constantly updating the patient partners. Because when we don't hear anything, this work isn't our job per se, but when we're not hearing those things, we want to know what's happening with the project. We want to know why it's being stalled. We want to know what's going on and that. I can say that I've been pretty fully involved in almost all of the projects that I've worked on over the years, and that communication is something that needs to be constant, even if it's just little details. As a researcher you know there's a lot of details and a lot of things, the “dot the I's and cross the T's” that have to be done during a project. We as patients wouldn't be involved in that project if we weren't interested in it. So we just ask researchers to please send us updates regularly. Ask us our opinions about these things. If you need us to pen a letter, draft the letter, do that stuff and we'll approve it and we'll sign it to make the process happen a little faster.

Anna

Thank you so much for explaining that. And there's so many important messages that you're bringing up in terms of regular communication, the need for accountability, checking in, and not being scared to ask patient partners and to be honest with them and to say, I don't know, what do you think? Let's solve this problem together. So I'm so glad that you've highlighted these messages. And my two follow up questions are:

Is there an actual structured process towards these review questions?

I know that's something we talk about a lot too, is the need to start evaluating projects. So I'm wondering if any interested listeners could benefit by learning a bit more about the types of questions that you ask. And then:

I also know from your website that every project that's involved with your network also has to fill out a patient engagement plan. So I wonder if somehow that fits into the evaluation process as well in the iterative cycle, and whether you've seen an evolution in the types of patient engagement plans that have happened over time?

Cathy

Yeah, one of the things that we ask of the projects is for all of the folks on the project take some training. We've actually developed a learning pathway in terms of a lot of the stuff we do. Melanie and her team have just developed a patient engagement toolkit and process. We ask that the members of all the teams have taken the training, because we sometimes have projects where patient partners are not part of Can-SOLVE but we still offer the training to them. When I first started being involved as a patient partner, there was core training that was done by CIHR, core modules one, two, and three. We actually sat down with the researchers and went through that training as a team together so that everybody was trained on that. We ask them about what types of training has your team taken, and certainly if they're working on an Indigenous project we ask that they take:

The San’yas training

The OCAP training

The Kairos Blanket training if it's available

View our storytelling module

View our knowledge keepers manual

We ask them to do those trainings, and we want to make sure that they are accessing all of the training that we've developed with Can-SOLVE, and people are accessing it and people are using it because it's extremely valuable as they continue on in their research career. And it's extremely valuable for patient partners to understand working in Indigenous communities, and how a research project works. As a patient, when something gets fixed, you want to know about it right away. So what's going to be involved in that?

Our patient partners are very much involved in the dissemination of the research project, throughout the project. I am the patient lead on the kidney check project, and I have probably done at least 20 different presentations to different groups all across Canada, internationally, and within the states. We’ve also started to do presentations to groups outside of kidney healthcare, we just did a presentation with the BDI technologies, and there were over 400 people in attendance at that. We do those things because it's about growing and scaling, and from the kidney screening project, we believe that it should be a public health matter if you're getting screened for kidney disease. As a woman, if you're getting a pap smear or mammogram and all of those things, you should also be able to get your kidney screen. So, you know, we're talking about public health issues in terms of expansion and all that. Arlene, my co-chair of IPERC, and an executive of the Patient Governance Council talks about the fact that we're ordinary people doing extraordinary work because we truly are, in terms of of everything that we've done and how we've done it, making things happen.

Having been involved since 2016, I often tell everyone that I wish I didn't enjoy the work so much because it does get really time consuming. But I was treated, I was screened, I'm now well, and it's my duty and it's my honour to continue to give back to my community and to give back to the kidney community and the researchers that I worked with and all of the people involved that are making such substantial differences within kidney care. And don't get me started on the new drugs that are out for kidney disease, because I'm so excited about that. In terms of the new drugs that have been proven to delay the onset of the need for dialysis by years, years! And that for kidney patients and those with diabetes and other things is so important to be able to access, and we need to get that message out to our communities.

Melanie

Thanks, Cathy. I was just going to mention, too, that part of the draw that brings patient partners to research and Cathy's kind of highlighted this, is giving back, or to use your words Cathy, that you're honoured to be a part of this kind of thing. And I'm constantly struck by how patient partners are so engaged. They want to be so involved, they want to give their time, and your contribution is so highly valued and valuable. I'm just so honoured that we get to work with you, Cathy, and other patient partners too. So thank you.

Just to get back to your question Anna, there is a process in how the projects are reviewed in the peer review process. There's a questionnaire and there's a project reporting process. The projects are asked to report on various aspects of their research, and that is standardized for all of the projects. It includes a section on cultural competency and Indigenous engagement, and it also includes a section on patient engagement and capacity building. So every project is accountable to describe how they have conducted this over the prior reporting year. We see this obviously ebbs and flows through the nature of the research, there might be more engagement in the initial parts and then it might change shape as they're implementing a survey, for example, maybe there's patients involved in going into for example, a hemodialysis clinic and walking through the survey with those patients at the clinic. The patient engagement will vary based on the nature of the trajectory of the research.

We also ask in those project review reports for the patient voice. So that particular section of the project report, we ask for the patient partners to be involved in writing that. So the patient partners who are co-researchers on those projects are involved in writing that piece of the report. And then when it comes to the feedback, we come back to have those project check-in calls and discuss the report and the review, that process is a little more organic. So we do have a preparatory meeting, where I meet with the patient partners who are part of our Patient Governance Council who will be attending that project review and we look back at the report that the project submitted and the peer review response to that report. We also request plain language summaries from the projects, and we review those plain language summaries too. And then from that we review all of that material, and look at ways that we can either find more information, because maybe there's a bit of a gap and we want to know more clearly how they went out and recruited their patient partners to be involved and/or whatever it is that they’re doing. Then we set up some questions and also some recommendations or suggestions for how they might strengthen the project or ways that the patient partners might feel they're more included or more valued or compensated or better ways for them to see the impact of their engagement.

We're kind of looking at it as a consultant when it comes to this piece of the puzzle. So it's really based on what's coming out of the report, what's coming out of the review committee's response to their report, and what we're seeing. Another really important piece is looking at how to take information from other projects that are doing really well with their patient engagement and knowledge share it across the projects. So just taking what's working well and sharing a little knowledge across those projects is another piece that I think is really valuable within our network and we have the opportunity to provide that support to the projects.

Another thing that I've been thinking a lot about lately in terms of patient engagement, is really looking at how we can encourage researchers to report on how they recruit patient partners. There seems to be quite a gap in the literature out there, and this seems to be something that I'm contacted a lot about, quite often by researchers looking for patient partners and also looking for advice or tips on how to recruit patient partners into their research. So I would encourage all researchers who are doing patient oriented research to also report on how they recruited their patient partners to their team.

Anna

Something I've been reflecting on as well about my own research program and how when I first started it was pretty scary, to be honest, to try to figure out how to recruit patient partners and where to go. And as our SPOR networks have grown and so have my own professional networks, it's been really nice to see the power of social media as well, and places like the Patient Advisor's Network having a way to post your projects onto their website and have it dispersed nationally. I've really, really enjoyed, not only being able to recruit from within Winnipeg, but across Canada. And I find it's the networks and the social media and the patient groups that are really helping towards that as well. Something that is also really striking me about all that you have shared is the depth of meaningful engagement within your network, both in terms of governance that ensures accountability and also

I was wondering whether you could tell us more about the underlying principles of engagement within your network as well?

And once you're done doing that, because I don't want to lose the thought:

Could you touch upon your whole idea of capacity bridging, which I believe you've alluded to in terms of cross-pollinating the wins across different projects so that they may learn from each other?

Cathy

I'll take on the first topic. When we talk about our core values, we talk about our six R’s:

Respect

Responsibility

Reciprocity

Relevance

Relationships

being Real

And those are the six foundations of how we work as patient partners and how we work as a network.

And so under respect, we acknowledge the land, the water and the territories always in our work. We have a land acknowledgement series, if you haven't seen it, it's narrated by one of our former members who has passed on that we really value quite highly. I love listening to her voice, and I love listening to Mary Beaucage and how she tells it so succinctly about land acknowledgments. And I have worked on projects or been on different groups that haven't done land acknowledgments, and I've always pointed them to that. And I've always asked them to please, if I'm going to be a member of this, I'm going to ask that you do a land acknowledgement at the beginning of your meetings. And the other part of respect is that we treat each other with respect.

In terms of responsibility, we are accountable. We support one another, we share the workload and we lead by example, and that's how we as patients work and that's how the team works. I always talk about our Can-SOLVE team, whether they're patient partners, whether they're core team, whether they're researchers and I'm extremely grateful to be on the leadership team. And I’ve learned more about the whole process than I maybe really wanted to learn, but it's a really interesting process in terms of of leadership, in terms of making sure from an Indigenous, First Nations, Métis, and Inuit perspective that we're doing things in a good way. And so that's why I really like being part of that.

It brings us to our third R which is reciprocity. We actively listen to one another and we practice circle work. We also practice within our group that we're not moving ahead until we're all ready to move ahead. We don't want to move ahead when half of the group is dissenting or doesn't want to. So we go around and until we're all satisfied with what we're going to do. So we work on a consensus model of how we work on each one of our committees. We do things working in a circle, such as the two-eyed seeing, which is really another core part. And we could probably do a whole session just on our two-eyed seeing and our Indigenous work and reciprocal learning, because it's not enough just for the patients to learn. I want researchers to learn. I want the core team to understand and I want everyone that we're working with to understand where we're coming from and doing things within a good way.

We also work on relevance, and relevance is putting our heart into work to benefit affected populations in terms of the work we do and how we engage with patient partners from underrepresented areas. We have areas of the country where we don't have patient partners, and we've worked extensively in the last two years to make sure that each area of Canada has representation.

I think the basis and the most significant aspect for me is the relationships. We work really hard to build those relationships and to build that trust because as patient partners you're not going to be able to share in a meeting or do anything in a meeting unless you feel safe. And so in order to do that, you must build that relationship. You must build that trust. And it must be a safe place where you can say what you want to say. You know, I've learned over the years to be able to get my point across without being mean or anything and do it as a learning tool for people. I try to work at building that relationship and helping them to understand where we come in as patient partners and what we're going to do.

We welcome new members on a regular basis and we're always out there looking for new members. It's just an ongoing process, developing the patient recruitment tool and learning toolkit for patients partners, and we practice open mindedness. I think that's the other thing that I have learned is to always keep an open mind. And it may not be the way that I think the project should go or whatever, but I need to keep an open mind to be able to help them, to understand where I'm coming from, and also to understand where they're coming from.

And the other thing is that we keep it real. That's our last R, that we speak our truth. From my perspective as a First Nation woman, I have always stood in my truth, and I very seldom talk about other people's journeys in terms of that. I understand things from my journey and how I handled things and what I've done, and I've heard a lot of different stories and all of those things, and I always stand in my truth and I share knowledge. I also have taken far more courses. I pursue educational, training and learning opportunities because whatever's offered to me, I'll go and I'll take that training to better understand how we work. A lot of our researchers now are taking a course, it’s an implementation toolkit people are taking on implementation of the data and everything, almost every team, if not every team, has their research manager or their associate that's taken this course. We ask them to take it to be able to understand how to mobilize knowledge and understand how to do those things.

So those are the six R’s and the core values of how we work as Can-SOLVE. We develop these with patient partners because we want everyone to be in an area where they feel safe. They feel that they're able to to comment without repercussions. We always have elders present within our groups, we always have a leader within our groups, and so if someone's offended or whatever, we deal with those things and we just keep moving forward in a good way.

Melanie

Thank you Cathy. That was a great explanation of the core values. And I'm so glad that you mentioned that these were really co-developed with the patient partners. And I know they apply to the patient partners and how the Patient Governance Council and IPERC work and they really form the fabric of the entire network. I strongly believe that everybody who's involved in the research projects in the Can-SOLVE network hold these core values to their heart. And it really shows when we get together in-person for our annual meetings or when we get together in-person and meet up with various members of the network in various capacities. All those R’s are present and it really shows through, and it creates a really safe space, as you mentioned, for working together, valuing everybody's opinions and recognizing how impactful the work can be when its meaningful engagement.

That really leads into this capacity bridging concept. I first heard about this term in a presentation by Dr. Charlotte de Lope and I've been really struck by it. It was almost like a eureka moment for me when I heard about it because I was struggling with how to recognize capacity building in a way that feels still like it holds on to all of those core values? I think when you use the term building, it implies that there was already something missing, and to me it felt like there was just something around the language being used. In terms of capacity “building”, that’s not really what we're doing because people are coming to this network with all kinds of capacities, and that's why we want patient involvement in the research. To keep it authentic, to keep it relevant, and to keep the direction going in the way that is most meaningful for patients and the people for who the research matters most, because we want them to have the voice at the table. So I was really sort of struggling with how to rectify this language, and then I came across this concept of capacity bridging. It was the perfect way to create this metaphor for how everybody's coming to the table with

expertise

life experience

professional experience

lived experience with illness

there’s just so much expertise at the table from all realms of their lives, and every voice at the table has an opportunity to share that knowledge. If we have it set up as a metaphor of a bridge, we can recognize that the information flow, the interactions, the communication, the knowledge, it can flow in all directions.

I mean, if there's two people at the table, it can flow bi-directionally. If you have people from all different realms of the research world and different stakeholders, it can flow in all directions. So it's something that the network has already been doing really well. And it just wasn't captured this way with the idea of capacity building, so I think calling it capacity bridging is just a nice way of recognizing that we aren't coming as blank slates to be filled up with with knowledge. The training that we offer was developed because there was a need, that gap was identified, the trainings were developed, and people take the trainings as the need is there.

There is opportunity to “build capacities”, so I don't want to negate that term completely, but we also want to look at how everybody's coming with various expertise and how we can really capture that. We want to build upon it and just strive to recognize that it's a true collaboration. Just to give an example, one of the things we do when patient partners are coming into the network, either as members of the patient governance council or patient partners who are getting involved on a research project as co-researchers on that project, we ask them to describe how they would like to be involved, and also what experience they might have in their career or past experience that could lend itself to provide some expertise in an area that isn't solely their lived experience with illness, either as a patient themselves or as a caregiver for a loved one. We want to focus on recognizing those additional skills that everyone brings to the table and working collaboratively.

Cathy

When our patient partners come to us we want to fully prepare them for when they're doing presentations, we fully prepare them for being part of a team with the training. I can't tell you how beneficial it was for myself, even though I've always done a lot of public speaking, to be able to gear my talk to my audience and how to do that. Through the storytelling module and through through working with the team at CAN-SOLVE, they always make sure that whenever I'm doing a presentation, whenever I'm out there doing things that I'm prepared and that I'm ready to do this. They also make sure that whether it's a PowerPoint presentation or whatever it is, I have everything that I need to go out and talk in a good way and to help people understand the topic that I'm talking about in an effective way. The storytelling module gave me that confidence.

What I would say in terms of helping those folks that work with patients and do presentations or stuff like that, is that when you're doing a presentation and you're talking about patients and those things, you need to make sure that you have a patient at the table with you during that talk. I have attended many presentations, and that is always my first question. If I look at who's presenting I want to know where's your patient? When talking about patient engagement, you need that patient perspective. That's why we're on teams, that's why we're doing these things. So you need that perspective as a patient to be able to help people, to understand why patient engagement is so important and why patient engagement improves research.

Anna

Thank you for those in-depth but accessible explanations. The six R’s and capacity bridging are definitely two of my key takeaways from everything that you've shared with us, and I definitely think the tagline for this episode will be “meaningful patient engagement”, because I've been really touched and impressed with all the different ways that the network has ensured that there is meaningful engagement in everything that it does. So as we head to the very end of our episode, the last two questions that I'd like to ask you is:

How do I become involved in your network, whether I'm a patient or perhaps a researcher or clinician? So I'm wondering, regardless of the knowledge user group.

And then I'm wondering:

Is there anything that you haven't shared about the network or any key patient engagement related lessons that you've learned along the way that you'd like to leave the listeners thinking about when they walk away from this episode?

Cathy

I think from my perspective as a patient partner, we have a lot of information on our website. A lot of our patient partners come to us through presentations as well as from our researchers, the ones that actually have clinics and are doing those things. We have a lot of information on our website and there's a lot of contact information if you're interested in becoming a patient partner. If you're interested in kidney research, whether you're a researcher, a patient, a donor, or someone with lived experience, there's many different ways to come into Can-SOLVE.

I think from my perspective, the lessons that I've learned is that doctors and researchers listen. They listen to and honour what you have to say. I don't think that there's been any researchers that I've worked with over the years that haven't said to me how valuable patient and my involvement in the project has been to them.

Last year, when I presented at the American Society of Nephrology in Philadelphia, I was doing a poster session and I was presenting our poster on the development of the Indigenous People's Engagement Research Council and Can-SOLVE. While I was there I noticed there were very few patient partners there at the time, and I'm hoping things are changing this year. Almost every one of the researchers or research associates that came up to me would actually thank me. When I said I was a patient partner they would thank me and say stuff like “I'm glad that you're involved” without even knowing me, and they understand how important it is for patients to be involved in research, how it changes the research question and how it changes the value of what kind of research that they're doing to improve the lives of of patients and their families and their caregivers.

I've been involved in Can-SOLVE from the beginning, and I've seen a wholesale change in how we've taken an organization and made it patient friendly and developed all of these tools to be able to help us and to be able to work fairly and to be doing things in a good way. And so to be able to see those changes and to be able to be part of it is really exciting for me to still be doing this work. I always say I'm going to leave next year, and every next year I'm still here. So whatever I can do, I mentor a lot of people, I keep moving forward, and I keep doing those things and keep encouraging people to stand in their truth and find their voice because Can-SOLVE, IPERC, and the Patient Governance Council have helped me to find my voice and to be able to go out there and get people to understand what patient engagement is and how truly valuable it is to the Canadian Research Network and international Network too. Miigwetch.

Melanie

One last thing that I'd like to touch upon is the key ways the patient partners find it to be a meaningful experience for them that we've found. I'll just mention the Patient Governance Council meets monthly and a large part of our meetings is around reconnecting with one another. So we meet by zoom because we're composed of patient partners from all across the country. One of the things that all the patient partners who are part of the Patient Governance Council always remark is how being a part of a group that is so welcoming is such an important aspect, and they even refer to the group as a family. And we've tried to kind of turn the lens inward and ask ourselves what makes the Patient Governance Council so special? Because it's this group of a dozen or so people, and we have lost some people over the years who have passed, and we have welcomed new members to the network, so it is a changing group. It's not necessarily a set group of people that have been with the network since its inception. Some have, Cathy is one, but this group, it's almost like there's an energy amongst the group that lives on despite the people who are involved. It's this magic of the group and we've wondered, what is it about the Patient Governance Council that's so special? And how can we write it down to promote it for others? And what what are the pieces?

So we've talked about things like that acronym team, T E A M: together everyone achieves more and how this group comes together and does these great things, they come together as a family as they describe it. I think what we've decided is it comes down to those core values that we mentioned and how it's real, it's respectful, and all of the R’s are just permeated within that group completely. It's that honesty and that opportunity to share your story and be heard.

When we reflect on why, I put this question to the Patient Governance Council: why are you a patient partner? A lot of the answers that came back fit into a few key points that I'll just share now. So one of them is that there was an opportunity they wanted, there was a desire to give back. This point in their health journey where there was the time, maybe the stabilization in their health, they found that now they were ready and they wanted to give back. So they received care or they felt that they wanted to help future patients, or help guide the research in a way that was an opportunity to give back.

Then also looking at how to make the participation meaningful. So the reason they stay as patient partners is because they find that their participation in the research is meaningful. However that transpires, whether that is recognizing the impact that they have through, for example:

Seeing the results being played out in the clinics that they visit

Seeing posters of research displayed

Seeing presentations

Seeing the effects of their participation (e.g., through changing paradigms of research or seeing the impacts in on the practical level).

As well, really taking the time to build relationships. So having that sensation or that feeling that you are a part of a group of people with the shared values, shared vision, and shared respect and all those R’s, and really taking the time to build those relationships. And from that there's trust that is developed. So feeling like they're a part of this group where they are valued and trusted. There's a mutual trust amongst all the members of the group. So it's a real leveler when you see the group of people together that are just people all working together with the same vision and goals.

Another key component is that they're recognized for their contributions. Even though many aren't doing it for the recognition, there's still something to be said for that recognition. So it's like an awareness that nobody can do this alone. It does take the full team to get there. That recognition and then what plays into that as well is being fairly compensated for their time. So when patient partners are volunteering to be a part of research, there's still a lot of time out of their day. Maybe they even take their holiday time from their day jobs to be involved in research. And just recognizing that their time should be compensated fairly. So building in a compensation strategy with patient partners as co developers of that strategy is also a key component to ensuring that the patients are valued.

Anna

Thanks so much for helping ensure that we wrap the project by tying everything back to meaningful patient engagement again. And I definitely think that another key ingredient that you didn't necessarily mention, but I definitely felt throughout our shoot together was the whole idea of love and warmth and caring. And you two are very clearly very kind and thoughtful individuals, and I'm sure that permeates through the network as well. So if it ever feels like in your report, you're missing something, I think that's the component, it's the heart piece. That's definitely irreplaceable and it's the bedrock of many, many wonderful networks.

As we wrap, I'd like to remind the listeners to check out our website, asperusual.substack.com, for resources from today's episode and interactive transcripts from this and previous episodes. While you're there, please be sure to subscribe to this podcast or you can do so wherever it is that you download your podcast episodes from. If you'd like to contact me, please shoot me an email at anna.asperusual@gmail.com. Lastly, if you feel that this podcast is a good use of your time, please do share it with your colleagues and friends. Once again, thank you so much Melanie and Cathy for sharing your time and wisdom on this episode, and to you, the listeners, for continuing to tune in. Until next time, let's be sure to keep working together to make patient engagement and research the standard or as per usual.